Meta-Pleasure

The Familiar, Volume 5: Redwood By Mark Z. DanielewskiPantheon, 2017 “Redwood”, the fifth volume of Mark Z. Danielewski’s 27-volume novel-in-progress The Familiar, marks a checkpoint for the series, the conclusion of its first five-volume “Season,” and as such there seems to be an emboldened tone here, something confident and validated. With this fifth 800+-page installment, there’s a clear feeling, on the author’s end, of accomplishment. The same can surely be said of fans who’ve been following along.The series juggles nine story lines, beginning in Los Angeles, Mexico, Singapore and Texas, that are all grounded by the central story of an epileptic and precociously inquisitive twelve-year-old girl named Xanther who, in the first volume, finds a small white cat in a storm drain. The soft mewing of the cat is heard by the leading character of each storyline, across the globe, as something small and distant but still close enough to find. Xanther is the only one who seeks it out. In Volume Two she takes this ostensible kitten to the vet and finds, from an examination of his teeth, that he’s actually quite old. Perhaps older than a cat can be. And so, little by little, we’re clued in to something supernatural about him. Xanther immediately falls in love with the cat and, in time, is changed by it. She’s more articulate, more calm. Her seizures no longer appear to be an issue so long as the cat is near. Animals at a private zoo accord her a strange deference. Her step-father, a video game developer named Anwar, marvels at her newfound savviness as a gamer, and at her reconstruction of a complicated match of the Chinese board game Go, her overall contentedness.But Xanther’s dependency on the unnamed cat, as well as his on her, seems to indicate, with each volume, a strengthening channel between them wherein things are given and taken. Xanther sees dark stones hovering over people’s eyes and falls into a strange meditative space that’s identified, by name and by visuals on the page, as a forest. Separation from the cat induces seizures and a mind-scrambling anxiety.Meanwhile, in Mexico, a drug kingpin called the Mayor is importing wild animals for rich people to hunt in confinement, and one of the animals has escaped. A witch in Singapore is heading to Los Angeles in search of her missing cat. An Armenian cab driver named Schnork is helping his friend, an academic, compile an archive of survivor testimonies from the 1915 genocide, wherein the Turkish government tried to kill the millions of Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire. Schnork’s devotion to the project seems to suggest an impending encounter with another main character, the Turkish detective Ozgur Talat, who’s investigating a strange series of murders around L.A., all of which seem to have some relation to the Apple-like tech company Galvadyne – which is interested in hiring Xanther’s step-father as a developer.It’s complicated to the point of opacity in the first volume. Slowly, however, the series opens up (in a reflection of one of its many motifs: the flinging open of doors, the bursting of cages) and starts pursuing, in earnest, the key to its own survival, which is to keep the reader turning pages, urgently, despite its daunting heft. As for

By Mark Z. DanielewskiPantheon, 2017 “Redwood”, the fifth volume of Mark Z. Danielewski’s 27-volume novel-in-progress The Familiar, marks a checkpoint for the series, the conclusion of its first five-volume “Season,” and as such there seems to be an emboldened tone here, something confident and validated. With this fifth 800+-page installment, there’s a clear feeling, on the author’s end, of accomplishment. The same can surely be said of fans who’ve been following along.The series juggles nine story lines, beginning in Los Angeles, Mexico, Singapore and Texas, that are all grounded by the central story of an epileptic and precociously inquisitive twelve-year-old girl named Xanther who, in the first volume, finds a small white cat in a storm drain. The soft mewing of the cat is heard by the leading character of each storyline, across the globe, as something small and distant but still close enough to find. Xanther is the only one who seeks it out. In Volume Two she takes this ostensible kitten to the vet and finds, from an examination of his teeth, that he’s actually quite old. Perhaps older than a cat can be. And so, little by little, we’re clued in to something supernatural about him. Xanther immediately falls in love with the cat and, in time, is changed by it. She’s more articulate, more calm. Her seizures no longer appear to be an issue so long as the cat is near. Animals at a private zoo accord her a strange deference. Her step-father, a video game developer named Anwar, marvels at her newfound savviness as a gamer, and at her reconstruction of a complicated match of the Chinese board game Go, her overall contentedness.But Xanther’s dependency on the unnamed cat, as well as his on her, seems to indicate, with each volume, a strengthening channel between them wherein things are given and taken. Xanther sees dark stones hovering over people’s eyes and falls into a strange meditative space that’s identified, by name and by visuals on the page, as a forest. Separation from the cat induces seizures and a mind-scrambling anxiety.Meanwhile, in Mexico, a drug kingpin called the Mayor is importing wild animals for rich people to hunt in confinement, and one of the animals has escaped. A witch in Singapore is heading to Los Angeles in search of her missing cat. An Armenian cab driver named Schnork is helping his friend, an academic, compile an archive of survivor testimonies from the 1915 genocide, wherein the Turkish government tried to kill the millions of Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire. Schnork’s devotion to the project seems to suggest an impending encounter with another main character, the Turkish detective Ozgur Talat, who’s investigating a strange series of murders around L.A., all of which seem to have some relation to the Apple-like tech company Galvadyne – which is interested in hiring Xanther’s step-father as a developer.It’s complicated to the point of opacity in the first volume. Slowly, however, the series opens up (in a reflection of one of its many motifs: the flinging open of doors, the bursting of cages) and starts pursuing, in earnest, the key to its own survival, which is to keep the reader turning pages, urgently, despite its daunting heft. As for  why Danielewski’s trying to hit 27 volumes: The Familiar is meant to mirror the shape and conventions of a television series. Every five-volume cycle is supposed to be a single season and, with each volume clocking in at around 60,000 words (Great Gatsby length, more or less), it’s got as much drama as two episodes. So Danielewski’s basically looking to write, single-handedly, a narrative with the scope and duration of a five-season drama – the last season having a little extra: a bit less than The Sopranos, a bit more than The Wire. Then there’s the significance of the number three: many of the book’s sections have a triangular structure in which the narrative begins in the present moment, steps back to trace a line of action leading up to that moment, and then carries forward. The major villain is named Alvin Alex Anderson (three names, all beginning with a triangular letter). Three times three equals nine, and we’ve got nine story lines. Nine times three equals twenty-seven. At a rate of two books per year, for thirteen years, we’ll get the last installment in the year 2027. Maybe that’s all gibberish, a gimmick, but it doesn’t matter. The Familiar is ferried along on the strength of its slowly-coalescing story and Danielewski’s brilliant manipulation of pace, the way he doles out information, his use of cliffhangers.This latest volume, “Redwood,” marks the end of Season One. It’s a checkpoint for the audience, which by now has a good idea of what all our characters are up to and some solid theories as to how they’ll end up crossing each other’s paths, and it’s an achievement for the author, who makes his pride in the project known with passages like these.

why Danielewski’s trying to hit 27 volumes: The Familiar is meant to mirror the shape and conventions of a television series. Every five-volume cycle is supposed to be a single season and, with each volume clocking in at around 60,000 words (Great Gatsby length, more or less), it’s got as much drama as two episodes. So Danielewski’s basically looking to write, single-handedly, a narrative with the scope and duration of a five-season drama – the last season having a little extra: a bit less than The Sopranos, a bit more than The Wire. Then there’s the significance of the number three: many of the book’s sections have a triangular structure in which the narrative begins in the present moment, steps back to trace a line of action leading up to that moment, and then carries forward. The major villain is named Alvin Alex Anderson (three names, all beginning with a triangular letter). Three times three equals nine, and we’ve got nine story lines. Nine times three equals twenty-seven. At a rate of two books per year, for thirteen years, we’ll get the last installment in the year 2027. Maybe that’s all gibberish, a gimmick, but it doesn’t matter. The Familiar is ferried along on the strength of its slowly-coalescing story and Danielewski’s brilliant manipulation of pace, the way he doles out information, his use of cliffhangers.This latest volume, “Redwood,” marks the end of Season One. It’s a checkpoint for the audience, which by now has a good idea of what all our characters are up to and some solid theories as to how they’ll end up crossing each other’s paths, and it’s an achievement for the author, who makes his pride in the project known with passages like these.

…most people want cages. Want their routine, their job, the hate-my-life song they think makes them sound strong. Most people don’t got the huevos to live outside.

Not a glowing bit of prose out of context, granted, but it showcases the volume’s tone. Then, from the perspective of another character:

One thing that never changes, you’ll see, is just how impudent children are when it comes to the immediate. They want everything now. Only a few grow up to understand how to know now without want. Will you?

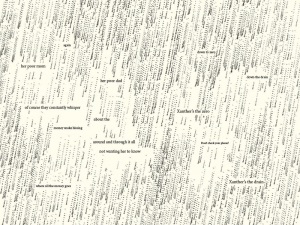

These remarks are pertinent to the story and its themes but they also ring true for Danielewski’s own sentiments, echoing his oft-mentioned championing, in public appearances, of patience as a reader, of mindfulness, of moving away from familiar things and embracing difficult and foreign texts, ideas, practices. And the author’s confidence is well-earned.The first volume, “One Rainy Day in May,” doesn’t do much to reward the reader’s labor, at least not the first time through. It’s strange, visually, and if you’re not endeared by graphic design or typographical hijinks, if you’re inclined to think, understandable, that the tricks and visuals are compensating for some narrative shortcoming and are thus reluctant to risk 800 pages of your time, then you’ll probably pass on The Familiar (although, again, the spacing makes each 800-page volume out to  something like 200 pages of prose). But Volume Two, “Into the Forest,” is better. Volume Three, “Honeysuckle & Pain,” is better still. By Volume Four the reader is moving swiftly through sections that, two books earlier, were a struggle; particularly those revolving around Jingjing, a heroin addict in Singapore whose narrative is told in a kind of pidgin language called Singlish. The novel’s propulsion, which is informed as much by the pacing of its prose as it is by a layout that sometimes puts only two or three words on a page, is one of the special delights.This is technically Danielewski’s fourth novel. His first was the postmodern horror opus, House of Leaves, followed by the time-twisting road novel Only Revolutions, and finally a svelte campfire story called The Fifty Year Sword. The books themselves are beautiful objects, whatever the strength of their content (I’m not a fan of Only Revolutions), and Danielewski’s monastic dedication to these long and intricate projects affords him a certain mystique. After The Fifty Year Sword came out in 2005, rumors took shape about a new Danielewski novel on the horizon, something big. Then there was word of a book deal: a million dollars for the first ten installments of a 27-volume novel. It was summarized, simply, as the story of a girl who finds a cat. Then the bizarre publishing scheme: two volumes to be released every year for thirteen years – the first volume being released nearly a decade after its inception.Then, with the release of that first book, we got the mythos of its ongoing production. The romantic picture of a writer at his peak, employing a sort of transcendental discipline to shape this monumental narrative while meeting a long series of deadlines. It’s difficult even to comprehend how he’s keeping the whole thing straight in his mind. Each successive volume, and ever re-reading of previous volumes in light of the new one’s revelations, shows an increasingly intricate and well-crafted design. Then there’s the task of collaborating with his crowd of translators (snippets of Arabic, Spanish and computer code are among the most common secondary languages to pop up),

something like 200 pages of prose). But Volume Two, “Into the Forest,” is better. Volume Three, “Honeysuckle & Pain,” is better still. By Volume Four the reader is moving swiftly through sections that, two books earlier, were a struggle; particularly those revolving around Jingjing, a heroin addict in Singapore whose narrative is told in a kind of pidgin language called Singlish. The novel’s propulsion, which is informed as much by the pacing of its prose as it is by a layout that sometimes puts only two or three words on a page, is one of the special delights.This is technically Danielewski’s fourth novel. His first was the postmodern horror opus, House of Leaves, followed by the time-twisting road novel Only Revolutions, and finally a svelte campfire story called The Fifty Year Sword. The books themselves are beautiful objects, whatever the strength of their content (I’m not a fan of Only Revolutions), and Danielewski’s monastic dedication to these long and intricate projects affords him a certain mystique. After The Fifty Year Sword came out in 2005, rumors took shape about a new Danielewski novel on the horizon, something big. Then there was word of a book deal: a million dollars for the first ten installments of a 27-volume novel. It was summarized, simply, as the story of a girl who finds a cat. Then the bizarre publishing scheme: two volumes to be released every year for thirteen years – the first volume being released nearly a decade after its inception.Then, with the release of that first book, we got the mythos of its ongoing production. The romantic picture of a writer at his peak, employing a sort of transcendental discipline to shape this monumental narrative while meeting a long series of deadlines. It’s difficult even to comprehend how he’s keeping the whole thing straight in his mind. Each successive volume, and ever re-reading of previous volumes in light of the new one’s revelations, shows an increasingly intricate and well-crafted design. Then there’s the task of collaborating with his crowd of translators (snippets of Arabic, Spanish and computer code are among the most common secondary languages to pop up),  graphic designers, consultants. Danielewski travels regularly to Singapore for research about the storyline that originates there. He interviews reformed gang members to inform the story of a kingpin’s bodyguard in Mexico, named Isandorno, and of a street-level dealer in L.A., Luther. Since the series’ renewal after Volume Ten is contingent on sales, Danielewski travels US cities twice a year, sometimes ten cities in a row, to promote each volume’s release (I actually saw him this year in Miami: nice guy, wears a hat). And then of course the deadlines are constantly looming and so he’s working on the airplane, in the hotel, everywhere. In California, where he lives and was recently married, Danielewski wakes at 5 a.m., eats breakfast and works out for an hour, gets to his desk at around dawn and works until dinner. He’s in bed by nine.The reason for pointing all this stuff out is that Danielewski – author, performer, approachable sage and postmodern wizard – is an integral character in the concept of The Familiar, the large project that goes beyond the book. Danielewski’s affable image and involvement with readers (granted: watch those Q&A videos and you’ll see he’s not always thrilled to be here) has cultivated a community of readers who engage with each other online and get excited by the team effort of decoding The Familiar’s mysteries. It’s fun. The books stand just fine on their own, and become propulsive almost to the point of agitation once a reader’s gotten through the hazing of Volume One, but the involvement with other readers a routine engagement with the author add to an experience that transcends the text.After reading Volumes 1—4, each upon its release, I participated in a newly-formed group (re)reading of the entire series on Facebook, comprised mostly of already-devout fans who were eager to go through the books again with some help, leading up to Volume Five’s Halloween release. The group is overseen by Danielewski himself, the scheduling mapped out by an assistant who also provides an occasional (verbose) discussion question. Example:

graphic designers, consultants. Danielewski travels regularly to Singapore for research about the storyline that originates there. He interviews reformed gang members to inform the story of a kingpin’s bodyguard in Mexico, named Isandorno, and of a street-level dealer in L.A., Luther. Since the series’ renewal after Volume Ten is contingent on sales, Danielewski travels US cities twice a year, sometimes ten cities in a row, to promote each volume’s release (I actually saw him this year in Miami: nice guy, wears a hat). And then of course the deadlines are constantly looming and so he’s working on the airplane, in the hotel, everywhere. In California, where he lives and was recently married, Danielewski wakes at 5 a.m., eats breakfast and works out for an hour, gets to his desk at around dawn and works until dinner. He’s in bed by nine.The reason for pointing all this stuff out is that Danielewski – author, performer, approachable sage and postmodern wizard – is an integral character in the concept of The Familiar, the large project that goes beyond the book. Danielewski’s affable image and involvement with readers (granted: watch those Q&A videos and you’ll see he’s not always thrilled to be here) has cultivated a community of readers who engage with each other online and get excited by the team effort of decoding The Familiar’s mysteries. It’s fun. The books stand just fine on their own, and become propulsive almost to the point of agitation once a reader’s gotten through the hazing of Volume One, but the involvement with other readers a routine engagement with the author add to an experience that transcends the text.After reading Volumes 1—4, each upon its release, I participated in a newly-formed group (re)reading of the entire series on Facebook, comprised mostly of already-devout fans who were eager to go through the books again with some help, leading up to Volume Five’s Halloween release. The group is overseen by Danielewski himself, the scheduling mapped out by an assistant who also provides an occasional (verbose) discussion question. Example:

[Danielewski] has said that THE FAMILIAR would have been “impossible to conceive had it not been for the sudden efflorescence of great television” (NPR interview). Now that there are four volumes and the finale for the first season is on the horizon (Oct. 31), compare your experience in reading this novel with your experience of watching one of the “big” televisual narratives such as THE WIRE, GAME OF THRONES, MAD MEN, or BREAKING BAD. What is it like to read a new volume every 6-8 months?....What are the similarities and differences between serial television and a serial novel in today’s media landscape?

Danielewski chimes in once a month, at the completion of each volume, for a Q&A. Hs answers are quick, often vague, but he’s there, engaged, and it sparks an enthusiasm for the series that’s as much to do with questions of its author’s accomplishment as the fate of the characters. The strength of “Redwood,” the fifth and most recent volume, resides mainly in the fact that Danielewski is paying his dues to the audience, and to the narrative, and while the graphic design and textual anomalies are off the charts in this one, with several passages carrying the series to new heights of abstraction, this volume champions the fact that its author believes, finally, that the novel, as an art form, is about story and character and feeling. Of our nine story lines, three exist in the same house. Xanther, her step-father Anwar and mother Astair, all haunted, in a way, by Xanther’s dead father, all of them tiptoeing around sore spots of the home dynamic (sibling jealousy, grief, the isolating complexity of either parent’s work, a tight money situation, sex) and, taken together, make for a compellingly rounded and tender portrait of a middle-class family. A hub of warmth around which the action and intrigue and suspense can safely orbit.There’s philosophy in these pages if you want it, and cultural commentary and math puzzles and beautiful art, but that’s icing. It might be integral to the story’s flavor, and to the idea of its physical heft and cosmic sprawl, but any wary reader can be sure that the story, finally, will be what draws her in and keeps her. No need for any savviness with math, or a polyglot at your side, no need to verse yourself in semiotics. Danielewski wants you to be intimidated by this text, but he also wants to reward and embrace the reader for confronting that intimidation. And that’s exactly what it feels he’s doing once you’ve caught yourself up in the tide.The Familiar is a complicated novel that is mindful of its own survival, which depends on its being fun and accessible enough to make readers want to buy it, not pirate or borrow, in the interest of funding its continuation. And it really is fun: the narrative on its own encompasses noir and science fiction, a bit of fantasy, highbrow domestic drama, there’s a healthy spatter of graphic sex and the action beats are hit with loyal consistency. After Volume Two, once a reader has learned the hows and whys of its pace, shape, and voices, the group discussion seems to agree: these volumes read quickly. Even tedious readers, pausing to parse and dissect the prose, fly through each installment in a few days once they’ve gotten the hang of it.

The strength of “Redwood,” the fifth and most recent volume, resides mainly in the fact that Danielewski is paying his dues to the audience, and to the narrative, and while the graphic design and textual anomalies are off the charts in this one, with several passages carrying the series to new heights of abstraction, this volume champions the fact that its author believes, finally, that the novel, as an art form, is about story and character and feeling. Of our nine story lines, three exist in the same house. Xanther, her step-father Anwar and mother Astair, all haunted, in a way, by Xanther’s dead father, all of them tiptoeing around sore spots of the home dynamic (sibling jealousy, grief, the isolating complexity of either parent’s work, a tight money situation, sex) and, taken together, make for a compellingly rounded and tender portrait of a middle-class family. A hub of warmth around which the action and intrigue and suspense can safely orbit.There’s philosophy in these pages if you want it, and cultural commentary and math puzzles and beautiful art, but that’s icing. It might be integral to the story’s flavor, and to the idea of its physical heft and cosmic sprawl, but any wary reader can be sure that the story, finally, will be what draws her in and keeps her. No need for any savviness with math, or a polyglot at your side, no need to verse yourself in semiotics. Danielewski wants you to be intimidated by this text, but he also wants to reward and embrace the reader for confronting that intimidation. And that’s exactly what it feels he’s doing once you’ve caught yourself up in the tide.The Familiar is a complicated novel that is mindful of its own survival, which depends on its being fun and accessible enough to make readers want to buy it, not pirate or borrow, in the interest of funding its continuation. And it really is fun: the narrative on its own encompasses noir and science fiction, a bit of fantasy, highbrow domestic drama, there’s a healthy spatter of graphic sex and the action beats are hit with loyal consistency. After Volume Two, once a reader has learned the hows and whys of its pace, shape, and voices, the group discussion seems to agree: these volumes read quickly. Even tedious readers, pausing to parse and dissect the prose, fly through each installment in a few days once they’ve gotten the hang of it. As such, cheesy though it sounds, there’s a meta-pleasure, maybe a morbid curiosity, in following The Familiar: wondering if the series will get renewed and wondering if, were he afforded the resources and time, Danielewski can make it to the end.Every long literary project seems to invoke an excitement in the reader that moves beyond the text. The question of whether Robert Caro will finish his biography of Lyndon Johnson adds a beat of excitement to its production, and the fact that he’s devoted most of his life to this project will afford that final volume an added grandeur. Same goes for George R.R. Martin’s glacial and nicotine-fueled progress through his Song of Ice and Fire (readers can at least rest assured that the fifty-something, martial arts-practicing, early-to-bed Danielewski is looking pretty healthy and sounding interested in his work).There’s a great delight to be found in The Familiar for those who stick with it, and in the larger community experience that surrounds it, and while there’s a chance that it’ll all grow tiresome, that the six- to eight-month gab between volumes will create a kind of fatigue, the series now has at least this contained unit of Season One to read through, parse, talk and geek out about. The same solace can be found in looking at those aforementioned series, by Caro and Martin: its continuation is suspect, things could fall apart, but at least, for now, we’ve got something good.Whether he carries the season to Volume Ten or 27, or quits it tomorrow, “Redwood” gives us a mostly-rounded text that’s worth celebrating.____Alex Sorondo is a writer and film critic living in Miami and the host of the Thousand Movie Project. His fiction has been published in First Inkling Magazine and Jai-Alai Magazine.

As such, cheesy though it sounds, there’s a meta-pleasure, maybe a morbid curiosity, in following The Familiar: wondering if the series will get renewed and wondering if, were he afforded the resources and time, Danielewski can make it to the end.Every long literary project seems to invoke an excitement in the reader that moves beyond the text. The question of whether Robert Caro will finish his biography of Lyndon Johnson adds a beat of excitement to its production, and the fact that he’s devoted most of his life to this project will afford that final volume an added grandeur. Same goes for George R.R. Martin’s glacial and nicotine-fueled progress through his Song of Ice and Fire (readers can at least rest assured that the fifty-something, martial arts-practicing, early-to-bed Danielewski is looking pretty healthy and sounding interested in his work).There’s a great delight to be found in The Familiar for those who stick with it, and in the larger community experience that surrounds it, and while there’s a chance that it’ll all grow tiresome, that the six- to eight-month gab between volumes will create a kind of fatigue, the series now has at least this contained unit of Season One to read through, parse, talk and geek out about. The same solace can be found in looking at those aforementioned series, by Caro and Martin: its continuation is suspect, things could fall apart, but at least, for now, we’ve got something good.Whether he carries the season to Volume Ten or 27, or quits it tomorrow, “Redwood” gives us a mostly-rounded text that’s worth celebrating.____Alex Sorondo is a writer and film critic living in Miami and the host of the Thousand Movie Project. His fiction has been published in First Inkling Magazine and Jai-Alai Magazine.