All the World to Nothing

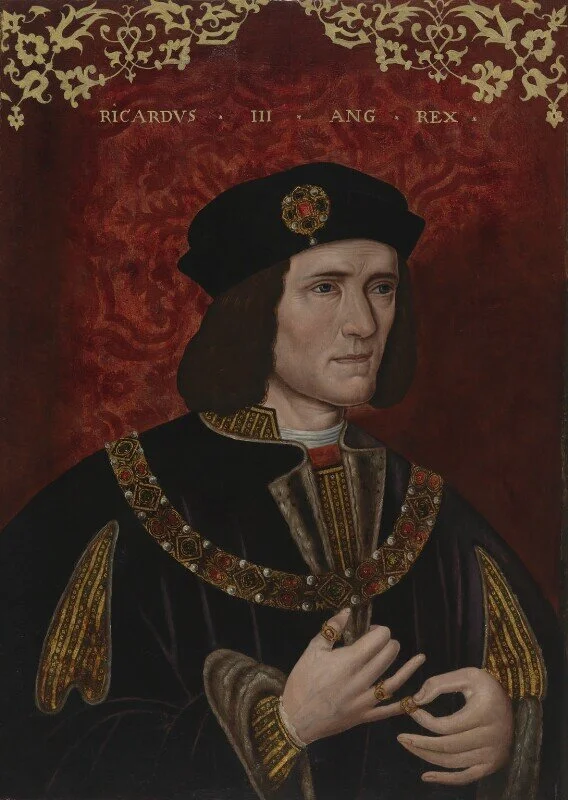

/It’s a face that has launched a thousand stories. Here is its most influential modern description:

It was as if the artist had striven to put on canvas something that his talent was not sufficient to translate into paint. The expression in the eyes—that most arresting and individual expression—had defeated him. So had the mouth: he had not known how to make lips so thin and so wide look mobile, so the mouth was wooden and a failure. What he had best succeeded in was the bone structure of the face: the strong cheekbones, the hollows below them, the chin too large for strength.

Was he a judge? a soldier? a prince?

Someone used to great responsibility, and responsible in his authority. Someone too conscientious. A worrier; perhaps a perfectionist. A man at ease in a large design, but anxious over details. A candidate for gastric ulcer. Someone, too, who had suffered ill-health as a child.

The observer, Josephine Tey’s Inspector Alan Grant, is shocked to learn that this portrait is of Richard III, infamous for usurping the throne from and then murdering his nephews: “Crouchback. The monster of nursery stories. The destroyer of innocence. A synonym for villainy.” Grant prides himself on his ability to spot a guilty man, so “to have transferred a subject from the dock to the bench was a shocking piece of ineptitude.” Thus Tey launches her 1951 classic The Daughter of Time, in which a bed-ridden Grant applies his investigative skills to one of the great unsolved historical mysteries—not the real fate of Richard’s nephews, the Princes in the Tower, but the character of Richard himself, the man who stands before the bar of history charged with their deaths.

Richard III was memorably presented by Shakespeare as the incarnation of energetic villainy. The opening monologue of The Tragedy of King Richard III establishes his insidious charm:

But I, that am not shaped for sportive tricks

Nor made to court an amorous looking-glass;

I, that am rudely stamped, and want love's majesty

To strut before a wanton ambling nymph;

I, that am curtailed of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time

Into this breathing world scarce half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them -

Why I, in this weak piping time of peace,

Have no delight to pass away the time,

Unless to spy my shadow in the sun

And descant on mine own deformity.

And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasures of these days.

Every other character in the play is insipid or foolish; none is a match for Richard’s wit and cunning. His powers of persuasion are most memorably demonstrated in his wooing of Lady Anne, carried out beside the coffin of her late husband Prince Edward— according to Shakespeare, one of Richard’s many innocent victims. Richard wins her over in a virtuosic display of sophistry and sheer unrelenting will, only to turn to us as she exits and disarmingly admit he’s playing only for the glory of the victory:

Was ever woman in this humor wooed?

Was ever woman in this humor won?

I’ll have her, but I will not keep her long.

What! I that killed her husband and his father

To take her in her heart’s extremest hate,

With curses in her mouth, tears in her eyes,

The bleeding witness of my hatred by,

Having God, her conscience, and these bars against me,

And I no friend to back my suit at all

But the plain devil and dissembling looks,

And yet to win her, all the world to nothing!Ha!

I love that gleeful “Ha!”: it enlists us, in spite of ourselves, on his side. Like Milton’s Satan or Thackeray’s Becky Sharp, Shakespeare’s Richard appeals and fascinates because he is a power player in a world of weaklings and sycophants. If he can win Anne, “all the world to nothing,” what else might he achieve? It’s hard not to wish his tepid antagonists would indeed die off, as he plans, and “leave the world for [him] to bustle in.”

The Richard of The Daughter of Time, however, is a very different man—and indeed Shakespeare’s chief source, Sir Thomas More—“the sainted Sir Thomas,” as Grant and comes, sneeringly, to characterize him—is one of Tey’s own antagonists. Tey, through Grant, imagines Richard as a man of conscience who found himself caught in an untenable conflict between his loyalty to his dead brother’s sons and his duty to his country. A man who both felt and inspired devoted love, this Richard paid for his painful choice to take the crown first with his life then with his reputation, as the enemies who betrayed and triumphed over him took control of the historical record: through their efforts he would be vilified for a murder of which, in Inspector Grant’s professional opinion, he was altogether innocent.

Tey’s Richard, though not as widely recognized as Shakespeare’s delicious blackguard, has nonetheless claimed his own lasting place in both literary and historical culture. But the appeal of this rehabilitated Richard III has eluded and puzzled some onlookers, notable among them historian Charles Ross. In his 1981 biography of Richard, Ross (who observes, with glancing disdain, that The Daughter of Time “was described by that fount of historical authority, the Daily Mail, as ‘a serious contribution to historical knowledge’”) notes that among modern defenders of Richard’s reputation, “the writers of fiction are the most prominent.” He cites Tey along with “a number of others, nearly all women writers, for whom the rehabilitation of the reputation of a long-dead king holds a strange and unexplained fascination.” (Is it just me, or do you also hear a faint echo there of Gilbert and Sullivan’s annoyance at the success of that “singular anomaly, the lady novelist”?)

There are, indeed, a “number” of women novelists who have followed Tey in revising, or at least revisiting, Richard’s reputation. A partial list of their books would include, besides The Daughter of Time, Rosemary Hawley Jarman’s We Speak No Treason (1971), Marian Palmer’s The White Boar (1968), Rhoda Edwards’s The Broken Sword (1971) and Fortune’s Wheel (1976), Barbara Willard’s young adult classic The Sprig of Broom (1971), Juliet Dymoke’s The Sun in Splendour (1980), Sharon Kay Penman’s The Sunne in Splendour (1982), Valerie Anand’s Crown of Roses (1989), Jean Plaidy’s The Reluctant Queen (1991), Reay Tannahill’s The Seventh Son (2002), Anne Easter Smith’s A Rose for the Crown (2006), Emma Darwin’s A Secret Alchemy (2008), Sandra Worth’s The King’s Daughter (2008), and Philippa Gregory’s The White Queen (2009). That this is not by any means a complete list of Ricardian novels confirms Ross’s impression that Richard’s story holds a certain “fascination,” not just for writers but for readers—among whom I have to count myself: of the titles listed, I own a round dozen.

My own preoccupation with Richard III dates to my first reading of The Daughter of Time in 6th grade. It would be hard to overestimate the book’s influence on me. Soon after reading it, I became a member (possibly, the youngest ever member) of the Richard III Society of Canada. I wrote my 7th-grade “independent research” project on Richard III; its 64 laborious pages of my best cursive writing include an annotated bibliography (on The Daughter of Time: “I don’t think it possible, no matter how anti-Richard you are to begin with, to finish the book anything less than sympathetic”; on Paul Murray Kendall’s 1955 biography: “Richard the Third is written in a descriptive, lively style, so, instead of being boring like biographies are apt to be, Kendall’s book is warm and gripping”). A few years later, on assignment for a night-school journalism class, I tracked down and interviewed Marian Palmer (author of The White Boar) - I think she was as much startled as pleased to be quizzed by an earnest 15 year old about the genesis of her 25-year-old novel. When I was in 10th grade, my sister’s History 12 teacher launched my lecturing career by inviting me to speak to their class about the case for Richard’s innocence. For a creative writing workshop, I wrote a painfully sentimental story about a devout Ricardian who encounters his ghost among the ruins of his home, Middleham Castle. A required element on the itinerary for my first trip to England, in 1986, was the Richard III memorial in Leicester, near the site of Richard’s final battle at Bosworth Field.

In my first year at university, I won a prize for a history essay analyzing Richard’s reign in light of Machiavelli’s The Prince. Then, as other interests crowded in, I didn’t think much about Richard again for a long time. Though I hung on to my Ricardian novels, I stopped buying new ones as they came out. Still, out of a perverse sentimentality, The Tragedy of King Richard III has always been my go-to play when I have the opportunity to assign some Shakespeare, and the reproduction of Richard’s portrait that my grandmother had framed for me many years ago hangs in my campus office. Surprisingly, no visitor has ever asked why!

I’ve recently been reconsidering my own “strange and unexplained fascination” for this long-dead king. My reflections were prompted by a recent biography of him by David Hipshon, part of Routledge’s ‘Historical Biographies’ series. Like the professional historian he is, Hipshon offers a clear, neutral account of Richard’s life and reign. He is more interested in the effect of Richard’s claiming of the throne and then defeat at Bosworth on the evolution of the English monarchy than he is in speculation about the Princes in the Tower. Their fate, he judiciously concludes, “we do not know, and are unlikely ever to know.” But Hipshon cannot entirely avoid the baggage his subject has picked up over five centuries of disputation, and so he concludes with a chapter on Richard’s “posthumous reputation,” rehearsing the central controversies while staying coolly detached from them.

Reading his brisk review made me think again about my Ricardian past and especially about my collection of novels, which are the opposite of cool and detached. What are they worth, what have they been worth to me, that I have kept them all these years? They’re mostly pretty limp literary specimens, after all—sentimental, clichéd, predictable. They’re also unbelievably similar to each other. To be sure, there are formal and stylistic differences. In some, Richard himself is the protagonist, in others his wife, or his best friend, or (a popular choice) his mistress. Some are third-person narratives; some are first-person; some use multiple narrators. Some start with his childhood, others begin during his brother Edward IV’s reign; others pick up only where the greatest controversies begin, with his claiming the throne at the expense of his nephews. But at bottom they are all variations on a single theme—Richard’s innocence—and a common premise, that Richard was not the kind of man to do what he is accused of doing. Anand’s Crown of Roses puts their basic position succinctly: “Richard was not a man who could order the deaths of former friends and not suffer for it.”

Overwhelmingly, the version of Richard’s character these novels offer is exactly that generated by Inspector Grant as he gazes on Richard’s portrait, and the novelists also share Tey’s preoccupation with reading that enigmatic face. Here, for instance, from Jarman’s We Speak No Treason (one of my favorites) is the first glimpse of Richard by the ‘nut-brown maid’ who in that novel becomes his lover:

He was solitary, young, and slender, of less than medium stature. His face had the fragile pallor of one who has fought sickness for a long time, yet in its high fine bones there was strength, and in the thin lips, resolution. His hair was dark, which made him paler still. He was alone with his thoughts. Ceaselessly he toyed with the hilt of his dagger, or twisted the ring on one finger as if he wearied of indolence and longed for action. Then he turned; I saw his eyes. Dark depths of eyes, which in one moment of changing light carried the gleam of something dangerous, and in the next, utter melancholy. And kindness too … compassion. They were like no other eyes in the world. Like stone I stood, and loved.

From Edwards’s The Broken Sword, here are the words of young Elizabeth of York, Richard’s niece and sister to the Princes in the Tower:

I was not sure what I wanted to read in his face—a hitherto undiscovered cruelty, guilt, were what I feared most. I saw none of these things; his face is not easy to read. … Once started, this study was hard to stop, and he occupied my mind a great deal. His mouth when he’s quiet and thinking, which is often, used to shut very firmly; now it seemed tight and hard.

Here’s Anne Neville’s first meeting with her future husband, in Plaidy’s The Reluctant Queen:

He was sitting alone and despondent. He was very pale; he looked tired and was staring rather gloomily straight ahead. ... Poor Richard! He was often very tired. When I saw him coming in wearing his heavy armour, I was very sorry for him. He was different from the other boys; they had more sturdy bodies. Richard never complained; he would have fiercely denied his fatigue, but I noticed it, and I liked him the more because of his stoical attitude. … I often thought what a brave spirit Richard had; and what a tragedy it was that he had been given such a frail body.

In Smith’s A Rose for the Crown, again it’s a woman’s hungry eyes through which we view Richard:

She watched Richard pace, twisting a ring around his little finger. He was calming himself. Certes, but he has self-control, she thought admiringly. His profile was strong: a prominent chin, straight, long nose and deep-set eyes. In repose his face looked stern, mostly on account of a thin straight mouth and long upper lip. But when he smiled . . . as he was now. [sic]

Reserved, honourable, with a hard-won physical toughness barely concealing a reservoir of emotional vulnerability: this Richard is the antithesis of Shakespeare’s robustly scheming villain. In his own way, though, he’s every bit as charismatic: these descriptions carry an erotic charge that distinguishes them from Grant’s more forensic interest. The masculine disdain for these books perhaps originates with this effect, which marks them as examples of the distinctly unprestigious genre of historical romance.

Richard’s characterization is not the only point of similarity between these novels. Specific incidents are retold over and over, and specific documents always need to be accounted for, from the enigmatic paper with only the signatures of the ill-fated Edward V, his uncle Richard (soon to depose him), and their cousin the Duke of Buckingham, to the poignant declaration by the City of York in August 1485 that “this day was our good King Richard piteously slain and murdered, to the great heaviness of this city.” Every novel works its way through what becomes a familiar checklist.

You might well wonder why there are even two such similar novels, never mind dozens. What’s the interest—where’s the payoff—after you get the basic idea? Good question. I think the answer actually lies precisely in all that repetition. There’s a literal reason for it: there’s a limited archive that provides the skeleton for any story to be told about this cast of characters. But even when we have a fair amount of information to go on—Hipshon observes about the period just after Richard’s ascension to the throne, for instance, that “Richard’s actions and his behaviour during this critical period can be fairly closely followed”—the most we can have is that bare-bones structure. Even during that well-documented interlude, “his motives ... are shrouded in mystery and controversy.” And it’s there, in that murky area between the facts, that the real action is. As long as there can be disputes over the why, the what will never lose its interest. The recurrent details of the historical record are renewed, refreshed, re-imagined every time someone else puts them into a new story, which can never be the story.

That’s true of all historical writing, of course: even when the evidence isn’t itself controversial (as much of it emphatically is, in Richard’s case), it doesn’t stand alone but needs to be assembled into a coherent narrative—and coherence means what makes sense to us, given our understanding and expectations of character and plot. That is, historical stories are still stories, still, in some essential structural ways, fictions. Eventually, in my academic research, I explored this issue of the blurring of genre boundaries through the work of theorists like Hayden White, Louis O. Mink, and Dominick La Capra. But long before then, I had seen it in action as I read and reread these novels and saw how they framed and reframed the few fixed points of our knowledge.

Am I really countering Ross’s dismissive remarks with a claim that these “lady novelists” are making a significant historiographical contribution? Well, yes, actually! No reader of multiple novels derived from the same source material could miss the lesson that history is not fixed, objective, or stable but malleable, imaginative, and interpretive. And I would also suggest that they are shrugged off by “real” historians like Ross for reasons that go beyond their complete and overt commitment to the fictionalizing that (while still essential) remains largely a covert operation in historical non-fiction. The line of genre they cross is also, particularly since the turn of the twentieth century, a gendered one.That territorial defensiveness is remarkably transparent in Ross. Here’s Hipshon’s astute summary:

These ‘historical novelists and the writers of detective stories’ were a group with a strange preponderance of females, which Ross could only view with suspicion. The novelists were ‘nearly all women writers, for whom the rehabilitation of the reputation of a long-dead king holds a strange and inexplicable fascination.’ By categorising Richard’s defenders in such a pejorative way, Ross did much to ensure that academic ‘professionals’ would hesitate to ruin their credentials by challenging the Ross orthodoxy.

At stake was not so much the facts as who had the right, the authority, to interpret them. As Hipshon concludes, Ross “took the view that defenders of Richard were largely a bunch of amateurs at war with the professionals.” Ross himself complains that,

Apart from an extraordinary sensitivity to any criticism of their eponymous hero, it has been a persistent weakness of the more extreme ‘revisionists’ to regard anything written about Richard III after 1485 as ipso facto discredited . . . Far too much of the pro-Ricardian stance rests on hypothesis and speculation, on a series of connected ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’, on the ‘may have been’, or even worse—the unacceptable historical imperative--the ‘must have been.’ … This has been accompanied at times by an unpleasant animus against academic historians, in spite of the fact that they have largely come to adopt a ‘moderate’ stance.”

That is, he objects, in part, to an excess of fictionalizing, as if every account of these disputed events doesn’t rely on interpolations.

His other objection is that the ‘revisionists’ are amateurs—not only that, but amateurs unwilling to defer to the professionals. As Hipshon rightly discerns, though, Ross’s view conflates ‘women writers’ and ‘amateurs.’ He doesn’t come right out and say that the little ladies should leave the real historical work to their menfolk, but in accusing his antagonists of “sensitivity” about their “hero,” in discounting their “fascination” (which in another context, with other participants, might reasonably be called “specialization”) as “strange and inexplicable,” he reinforces pejorative assumptions about women and about the kinds of books they write and enjoy—both, it seems, are equally weak, irrational, and romantic.

He couldn’t have made quite this case against “revisionists” before 1900, when almost every participant in the debate about Richard’s story was male. There was one prominent exception, Caroline Halsted, who published a two-volume biography in 1844. (In his book The Year of Three Kings, Giles St. Aubyn notes that “Miss Halsted’s Richard III is a pioneering work, mellifluous in style, romantic in tone, and charitable to a fault”; in his own biography of Richard, Paul Murray Kendall credits her with doing “some valuable digging in Harleian MS. 433” and other archival work, but overall concludes that “her work is conceived rather in the vein of the Victorian gift-book, and to this rude age is almost unreadable.”) Halsted’s presence, though, only highlights the reality of women’s marginalization in historical scholarship (as both writers and as historical agents) until well into the twentieth century—something that, again, I studied as an academic long after being exposed to its effects. (I even wrote a book about it.) The “unfortunate divide” Ross acknowledges emerging in the late nineteenth century “between the specialist and the popular views of Richard, which is almost the same as saying between the amateur and the professional,” is actually part of a wider phenomenon formalized by women’s exclusion from universities and thus from the kind of authority Ross invokes when he mentions “academic historians.”

Ross clearly sees the women writers who have taken up Richard’s cause as trespassers. In this he joins a long line of men who have tried to chase women off their turf using very similar rhetoric. In my book about women and Victorian historical writing, I quote an 1855 reviewer who “plead[s] guilty to a great dislike to the growing tendency among women to become writers of history”:

These authoresses, often gifted as they are with a certain insight into character, a vivid appreciation of individual facts and a great facility of narration, have in our opinion no historical grasp—no powerful comprehension of events; and what they produce is at the best but a pretty phantasmagoria of coloured figures.

Insight into character and facility of narration might sound like good things, but to this nineteenth-century reviewer they are symptoms that people are writing history “who ought to be writing novels.” For him, fiction was an acceptable form for women to tell historical stories because it lets them have their fun without challenging his authority. Over a century later, Ross apparently felt the same about the women writers he contemplated—or he would have, if, ironically, their ‘pretty phantasmagorias’ hadn’t, against all the rules, established the version that would win out over all the others. Ha! Even if they aren’t the best novels ever written, is it any wonder I’ve always been on their side?

Reconstruction of richard iii’s face from skull recovered in leicester

And therein lies, I think, the real source of Richard’s insidious charm. After five centuries and countless tellings and re-tellings, his history is as mysterious and inviting as ever because it has never been just about him—it has always also been about us. When we look at his enigmatic portrait, we see our own faces reflected back in the glass, after all. It’s our own shadows we spy in the sun, and as we descant, it’s our own deformities that reveal themselves: as much as any objective knowledge, it’s the twists and turns of our personalities and values that urge us towards one story rather than another. There was a real Richard, once upon a time, but our relationship now is with the Richard of our imaginations: what we see when we look at his portrait depends on what’s already in our sights. As for me, after all these years I still see what Inspector Grant’s long-suffering nurse finally sees too: “When you look at it for a little it’s really quite a nice face, isn’t it?”

Rohan Maitzen teaches in the English Department at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She was a senior editor at Open Letters Monthly and blogs about literature and criticism at Novel Readings.

.