On Finding a Copy of Ovid’s Fasti at the Local Goodwill

/From kingdom to republic to empire, the ancient Romans have transfixed the imagination of the ages, inspiring bestselling novels, plays, poems, movies, and TV productions (not to mention several nations and more than a few dictatorships). Throughout 2009, Steve Donoghue will trace their pomp and circumstance in "A Year with the Romans."

____I am the woman to whom you used to promise heaven.Alas, this is what I get instead of heaven

It’s a big one, the Goodwill I go to. It’s in a warehouse down by the Medical Center, and when you hold your breath past the hardcore smokers outside and walk through the front door, the size of the place nearly overwhelms you. This isn’t a mere storefront; it’s a vast aircraft-hangar of other people’s detritus.Along the west wall are the larger things – furniture, book cases, yard work implements in various states of disrepair. But the main traffic is in cheap clothing (“dead people’s clothes,” one appalled friend characterized them, although that’s hardly always the case), and the main shoppers are wheezing, hugely overweight women in late middle age, many of whom seem to know each other and all of whom come here on weekdays and weekends, shopping for Valentine’s Day or Saint Patrick’s Day or Easter or Christmas, celebrating some child’s birthday or anniversary – whatever occasion the calendar provides for treating themselves or their loved ones to some affordable apparel, or a slightly chipped nightstand, or a slack-strung tennis racket.Way in the back, in the northeast corner nearest the exit to the loading dock, are the books.The size of this section varies from Goodwill to Goodwill, but it’s never very big – a dozen shelves is usually the extent of it. The hardcovers are cheap, the paperbacks even cheaper, and only the sketchiest of attempts at organization are ever maintained (kids books can usually be found together, for instance, but probably only because kids books are easy to identify as such), so you have to browse.The grimly lockstepped homogeneity of the American reading taste is nowhere more graphically illustrated than in the book section of a Goodwill. Here the two dozen authors average working-class Americans (or, as they’ve come to be called in the last eight years, “poor people”) actually read get their weirdest, most accurate tribute; here are books that have been lovingly, intensely used.

|

Danielle Steel. Tom Clancy. Nora Roberts. Anne Rice. W.E.B. Griffin. Goodwill after Goodwill, shelf after shelf, they’re here: pages folded down, spines lined from hours and days spent lost in their rather tepid imaginings. In this section, naturally, there is no distinction between authors who are and are not in print; for every James Michener, there’s a Taylor Caldwell, all sun-faded or dog-eared in similar ways because somebody, somewhere, perhaps years ago, gained a little surcease from the cares of the world, then stuck an old sales receipt in at the back as a makeshift bookmark and … what? Lost the house? Cleaned the attic? Died? |

By whatever series of changes, they end up at Goodwills like mine, alongside outdated refrigerator repair manuals, nature books with half the color plates torn out, squat little Readers Digest omnibuses, dutifully highlighted oversized textbooks, abandoned diet books, and all the other items you’re unlikely to find in other venues. And mixed in with these things will regularly be the things I go there for: perfectly presentable copies of workhorse titles I love to give as gifts. These are books of genuine merit that, due to their publishers’ optimistic distribution schemes twenty and thirty years ago, exist still in abundance in the used book world. Mark Helprin’s Winter’s Tale, Tim O’Brien’s Going After Cacciato, Mary Renault’s The King Must Die, John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor, Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation, Kathleen Windsor’s Forever Amber, Bruce Catton’s This Hallowed Ground … these and about two dozen others turn up with encouraging regularity back on those shelves near the loading dock, and they’re cheap enough so I can buy them without even knowing what audience will eventually receive them.None of the harried mothers and wheezing old men who occasionally glance at those shelves is ever interested in these titles. They might pick up a Tom Clancy or a Danielle Steel, but only as printed reminders of years now long gone, when brains were nimble and reading brought joy. Nowadays, if they look at the Goodwill’s books at all, they look for business tracts promising them quick millions if they’ll just make a few crucial decisions; I mostly have the browsing to myself.Sometimes these workhorse titles I like to give as gifts are supplemented by still-serviceable copies of more canonical works. It’s always a treat to come across a Dickens or a Thackeray, or even an unsoiled Conan Doyle – the basics are always worth giving, and, the American educational system being what it is, they’re very often needed.They might be worth giving, these books, and they might be needed, but what they aren’t is surprising. I see them and their cousins all the time at my Goodwill, right next to the Candace Bushnell and the Al Franken. But the other day I had a shock while routinely scanning their titles on those back shelves: I found a copy of Ovid’s Fasti, in an Indiana University Press paperback, translated by somebody named Betty Rose Nagle. For one second, my mind couldn’t process what my eyes had taken in; I smiled and thought, “Well hello. What possible journey could have brought you here?”

This was meant to be. Your own fault hasn’t banished you,but a god; you have been exiled by an outraged god.You are not suffering your just deserts, but a deity’s wrath.Innocence is worth something in times of trouble …

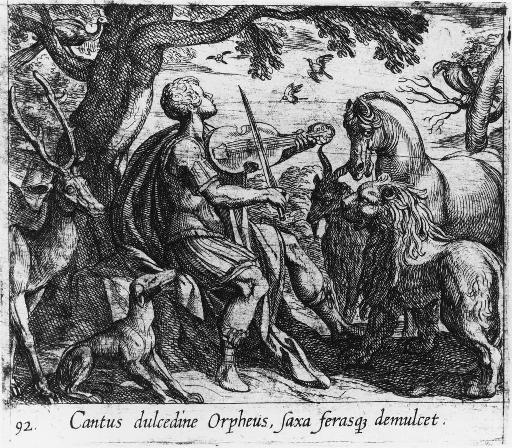

The Fasti originated 2000 years before that Goodwill opened its warehouse doors, six thousand miles from those back wall bookshelves. Publius Ovidius Naso, who in A.D. 8 at age fifty was the literary toast of ancient Rome, wanted his Fasti (and his nearly-finished Metamorphoses) to signal an artistic change; for decades, he had delighted and titillated the smart set in the city with his erotically subversive elegiacs, as metrically sumptuous as they were morally suspect. In work after work – the Amores, the Heroides, above all the inflammatory Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love) – he had exquisitely satirized the strictures of straitlaced morality Rome’s sole master, the emperor Augustus, was always trying to impose on his unruly citizenry. And the scandal industry had been good to Ovid: he was on his third wife, had a fiery-tempered daughter, and enjoyed financial freedom enough to spurn the handouts of powerful arts patrons like Maecenas. His books were in all the shops at the base of the Esquiline, and editions with smutty illustrations could be had cheap in the Subura. Second hand copies were everywhere in the ramshackle emporiums down by the riverside warehouses.He wanted more. He had emerged as Rome’s foremost literary figure – Catullus, Propertius, Tibullus, Virgil, Horace, were all gone by now – and like so many famous writers, he could bear being cast in marble provided the pedestal was high enough. Warlike epics were beyond his scope, as he readily admitted, but he could sing of other things, slippery, happy things like the changing of virgins into trees, or the year’s crop of holidays whose various laughters he knew so well. He conceived a grand work of elegiac couplets, a work explaining and celebrating all the feast-days, the Fasti of the Roman calendar. This work, and his Metamorphoses (in which he used the more heroic hexameter), would be his passport to Parnassus.

But in A.D. 8, as one writer puts it, “the disaster of his life befell him.” He was ordered by Augustus to quit Rome and go to Tomis, at the furthest northeast corner of the empire’s reach, in what is now Romania. A thunderbolt from the sky couldn’t have shocked Ovid harder. Rustic life held no allures for him as it did for Horace and Tibullus; he was city creature to his bones. Faced with the emperor’s implacable decision, he packed what he could and underwent this most unwanted of transformations. Just getting to Tomis took nearly a year by land and sea. His first night there must have been breakingly bitter. And how much worse the following morning must have been, the first in fifty years without the city’s civilized songbirds and the sounds of servants cleaning up after last night’s friendly gathering? Instead, an alien sunrise and gawping locals.

I have witnessed the talismans of Trojan Vesta moved from her dwellingto safety. Romans of course suppose gods are somebodies.But if they looked around at the stronghold where you residethey would know that no help is left to repay concern for the godsand that incense offered with a careful hand is a waste.

It’s ironic: despite the fact that Ovid spent the rest of his life writing about his exile (he was never recalled, neither by Augustus nor his successor Tiberius; he died at Tomis), we still can’t be completely sure what caused the emperor to banish him. “Carmen et error” Ovid says – he was sentenced to relegatio for “a poem and a mistake.” What the poem was is easy enough to guess, since the Ars Amatoria must have rankled Augustus, especially in light of the sexual scandals that swirled around his granddaughter Julia. What the error was is less clear and will always remain so. Ovid says his eyes betrayed him; if he’s being literal, what could he have seen that would prompt Augustus to send him so far, so permanently away? Did he witness some carnality of Julia’s and say nothing? Did he perhaps facilitate that carnality? Did he (as some classicists have drolly speculated) spy the empress Livia in the bathtub? Ovid writes verse after heartbreaking verse from his exile, apologizing and pleading for forgiveness, but he’s so sure his offense is common knowledge that he never thinks to make it explicit (or else he doesn’t wish to re-open old wounds) - and so we wonder.I wondered still, reading Betty Rose Nagle’s Introduction to her translation. The book was in perfect condition, unmarked, un-highlighted, unbroken amidst the moldy and yellowing outwash of so many cellars and garages, a sleek and sophisticated thing, distinctly out of place in its slightly shabby surroundings. What was it doing in this wild place, where three-day-old newspapers drift into doorways and dud lottery tickets litter the ground? These are Ovid-questions, and yet he never tells us what brought him to ask them. In that Introduction, Nagle wonders if perhaps the poem was the mistake (“it is possible,” she tells us, “for a Latin phrase such as carmen et error to mean ‘the mistake of a poem’”), and perhaps she’s right.Although it meant so much to Ovid, it means little to us. His exile changed everything about his life except the heart of it: he couldn’t stop writing. He composed his Tristia (Sorrows of an Exile), his Epistulae ex Ponto (Letters from Exile), his Halieutica (a fascinating Metamorphoses-like work on the various aquatic creatures of the Black Sea, a poem of which only tantalizing fragments remain), his Ibis (an angry screed in which his urbane poise is momentarily dropped, albeit without naming names) … he wrote an epithalamion for a friend, and he wrote verses, now lost, in the guttural tongue of Tomis, the hearing of which all day long had caused him, he claimed, to forget his Latin.

And he worked on the Fasti, these six books of elegiac couplets on the sprawling mythology undergirding Roman civic life (what of that mythology he couldn’t use, he discarded, and what was lacking he invented), adding incremental reworkings that weren’t finished when he died. Some of its verses are addressed to Augustus, others to that noble prince Germanicus, still others to the new emperor Tiberius, and some of its devices are repeated with an ungainliness Ovid would never have allowed to stand in a revised edition. As it is, we have the work – begun in such happy days, continued inside an unthinkable tragedy – frozen forever in mid-alteration.The design of that work would be a difficult thing to manage well, since the quick, coy glitter of Ovid’s couplets is an unlikely fit to the grand scope and length he envisioned, and it’s even more difficult to translate into English, a barbarian tongue even Ovid never imagined. Critics over the centuries have been of mixed opinion as to the success of the Fasti, and it’s fair to say it hasn’t received anything like the praise and attention successions of scholars and poets have given to his other works. This is odd, since for most of the work the revising Ovid-in-exile forgets to dwell on his misery and instead often gives us the summery immediacy of his best verse. Here’s Nagle’s version of Ovid singing the praises of the Anna Perenna festival in mid-March, when happy revelers indulge in wine and song along the Tiber banks:

They sing whatever they’ve learned at the showsand wave their hands nimbly along with the words.They set the punchbowl aside and perform crude reels, and a stylishgirlfriend lets down her hair and dances.They come back home staggering, a spectacle for the masses,and the crowd they run into calls them lucky.

By the time he was reworking the Fasti, first to praise his banisher, then to flatter the favored prince, and finally to reassure the new lord of the world that a simple poet posed no threat, how sweet and painful must have been the memory of the Anna Perenna for Ovid. The whole time he was revising this poem, slipping in favor-currying mentions of every important person he knew who might have a chance of convincing the emperor – either emperor – to call him back home, or even to order him to some warmer and kinder location on the Roman map. Nothing worked; no word from Rome ever came.

Time slips away and we grow old in the course of the noiselessyear, and the days, unbridled, run away.

In the Metamorphoses, Ovid had predicted his own literary immortality, although he could scarcely have imagined the refining fire he would pass through first. As one classicist put it, exaggerating only a bit, “exile broke him.” His art, and the charming, abiding curiosity that so informs the wanderings of his verse, never left him, but these must have been chilly consolations while he picked his way along the marshes of the Black Sea, stumbling through talks with fishermen in broken Getic, huddling under dirty blankets for days while winter storms blew themselves out over black, brackish waves. He wrote a great deal during the two decades of his relegatio, but it was all for performance – of the man’s inner sufferings we know nothing, and that’s probably a mercy.

And he was right: he did become immortal. Manuscripts of most of his works survived the Dark Ages that followed the fall of Rome, survived the march of armies and the rise and fall of nations, survived the burning and burying of libraries, and those works – the Tristia, the Heroides, above all the Metamorphoses – set the world ablaze when they were rediscovered at the birth of the Renaissance. Chaucer, Tasso, Ariosto, Spenser, Milton, and of course most of all Shakespeare – these and a host of other architects of Western literature used the bricks of Ovid for their raw materials, pilfering what they could not translate and translating what they could not pilfer. Even the Fasti received some attention (Frazer’s huge commentary on it was almost as long as his Golden Bough, and very nearly as definitive), although it’s always been a rarer thing, happening upon a nice edition of it.The Metamorphoses I’d expect to find, at that big Goodwill by the Medical Center. Probably it would be Horace Gregory’s great 1958 translation, and I’d snap it up to hand to some smart undergraduate who’d yet to make Ovid’s acquaintance. But the Fasti, that uneven and problematic work, celebrating festivals so far removed from the ones bargain-hunters now observe? That would be a much rarer occasion, a burst of improbability sufficient to alter the shape of a whole day.I took up that volume, translated by Betty Rose Nagle for Indiana University Press, and I thought of Ovid, writing and revising it 2000 years ago for an audience he would never see. I imagined the journey that book must have taken to end up on a shelf in that northeast corner, and I remembered that books, too, can know exile.I said “Well hello” and brought Ovid home.___Steve Donoghue grew up in Boston during the smallpox outbreak of 1689. He stills bears the scars from the disease and consequently bides most of his time in basements and shuttered studies, where he reads, writes, and hosts the literary blog Stevereads.