And a Tree

/There Are Birds

by John TaggartFlood Editions (2008)

An empty landscape: then, there are birds. As we read, a scene is completed, line by line (layer by layer). John Taggart’s poetry makes us aware of this process of “seeing”; instead of the canvas (or the vista), which is beheld all at once, writing makes a scene by addition. First there is red, then wheel / barrow; then, we learn, the wheelbarrow is “glazed with rain / water”; then that the wheelbarrow is located “beside the white / chickens”: now we know what so much depends upon, and we know its present state.

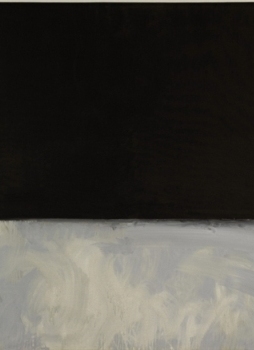

Do you recall watching a document, maybe even an image, as it was made by a dot matrix printer? Line by line (layer by layer). In previous books, Taggart revealed (unveiled) images and ideas by a deep repetition—repetition with significant variation, as exemplified by the first six lines of “The Rothko Chapel Poem” from Loop (1991):

Red deepened by black red made deep by blackprolation of deep red like stairs of lavadeep red like stairs of lava to gather us ingather us before the movements are to be madered stairs lead us lead us to three red roomsrooms of deep red light red deepened by black

|

Rothko’s work, in particular his most massive canvasses which surround the viewer and reveal a depth of color from undercoating, is a perfect companion for Taggart: both reward contemplation but go a step further, insisting—nay, forcing—the viewer/reader to slow down. It is impossible to read “The Rothko Chapel Poem” quickly and “get the gist” of it, since the gist is slowness as much as anything else. In “Odor of Quince,” from There Are Birds, Taggart describes his own process via Rothko—a Rothko re-imagined as a custom-auto painter working to make a Cadillac pink: |

|

a long job it takes a careful Rothko kind of character you have to

know what you’re doing

careful and serioustwenty-three coats of pink is serious

one after another one coat which is lightly sanded/hand-

rubbed another

coat lightly sanded/hand-rubbed

twenty-three coats

a long job it takes time for a coat to dry

you have to take a break take your time step back sit down have

a smoke

you have to think about it

The repetition that occurs so regularly (compactly) in “The Rothko Chapel Poem,” has been less regular (compact) in Taggart’s poetry since When the Saints (1999), but the attendant cadence remains unchanged. A poem from the new book sounds like a poem from Loop. Which leads me to believe that Taggart found—by trained instinct—a cadence that allows for great variation/improvisation. The Taggart cadence won’t go stale. (Imitations of Taggart’s poetry fail when all the focus is placed on repeated phrases, rather than on the music of the line.)

The centerpiece of There Are Birds is the 62-page “Unveiling / Marianne Moore.” My first encounter with this poem was at a reading, at which Taggart said, “This is a poem about Marianne Moore, myself, and a tree.” He read the epigraph which appears in the book: “In the words of Hsieh Ho, the first of the six laws is called animation through spirit consonance” (or, as Prince put it on Graffiti Bridge, “there’s joy in repetition”); he followed this epigraph with another, tailored for the reading: “In any project for poetry, the first effort should be devoted to establishing that poets are men and women, not writers” (Wallace Stevens). The poem begins “Skinny tree sparsely branched lacking / a felicitous phrase to begin”; the poem begins with a single, unimpressive tree and with a humble (personal) concern: where to begin?—though the personal concern is the concern of a writer, the admission “lacking a felicitous phrase to begin” admits a failure on the part of the writer, which emphasizes that poet-Taggart is a man, burdened with flaws/crosses to bear.

To assume Taggart had truly lacked “a felicitous phrase to begin” would be foolish. The tree lacks, not the poem. The tree simply begins, awkward as any birth, as puberty. And so the poem begins, without obvious drama, with a simple focus, and without a hook. This last lack is refreshing.

|

In “Unveiling / Marianne Moore,” Moore is a source; the poem contains biography, but is not a biography; what is unveiled is not Moore—unveiling is the process. Moore is the source which frees Taggart to write about anything the source leads him to: trees, himself, or even, Marianne Moore. Or fictional detectives, or naturalists, or Taggart’s homestead, a landscape that, in both There Are Birds and his previous book Pastorelles (2004), serve as a Giverny for Taggart. When he says his poem is “about a tree,” he means many trees, and flowers, and the foundation of a mill, and a covered bridge, “Saved from quaintness from the antique the ‘collectible’ / by use still in use the plank runners worn smooth / by traffic.” It would be easy to say these books are more personal than the rest, but they are not: they are only more obviously personal.

|

And that is why they might appeal to a larger audience than Loop, or Standing Wave (1993) , or Crosses: Poems 1992 – 1998 (2005). Greater appeal without compromise: the cadence remains.

There Are Birds begins and ends with mournful memorial poems. Robert Quine was a guitarist who played with Lou Reed, Richard Hell & The Voidoids, John Zorn, Tom Waits, and numerous others; he committed suicide by overdosing on heroin in 2004. In “Refrains for Robert Quine,” Taggart avoids writing directly about Quine; Quine is once again the source:

There are birds there is birdsong

having come through hunger and danger

there is free song

a free weaving of many songs

song against song and other songs clustered / spun out in a

blending of wavy pitches

tant

doucement the phrase means what the songs mean

freshness

that meaning so sweetly and freely as a gardener weaves flowers in

her hair.

The last poem is “Show and Tell / Robert Creeley” (followed by two “cadenzas”—“brilliant flourishes” which return to “Refrains for Robert Quine”). A memorial but also a love poem: “this poem is a song an / act / a work of love.” (Creeley died in 2005.)

“Grey Scale / Zukofsky” gives us Louis Zukofsky as image (object). Zukofsky is a photograph—“The great photographs are black and white and middle grey”—photographers, poets (Williams and Pound) are named and quoted, whereas Zukosky remains an image, “the one/only photograph on my wall”—by being the “only photograph,” it’s the most important photograph. However, Taggart does not commit to Zukofsky being the most important poet (mentor) in his life: “and going/getting past the question of who’s the fairest of them all // of them all watching over me // after a or the or // neither.”

There is a sense of humor that is Taggart’s own, that is very funny, and that is very much present in this book. High and low art happily commune here. Taggart’s cadence is perfect for comedy; comedy = timing, which is akin to meter, which is akin to cadence. In a note at the end of the book, Taggart asks that readers read the poems aloud, and that they do not ignore “space gaps of varying proportions (varying durations of silence).” He explains that they “provide time for rest, for an image to assume depth and definition, for reflection.” Read aloud the quote from “Odor of Quince,” following Taggart’s advice, and see if you don’t laugh when you read, “you have to think about it.” Maybe it’s wry, and certainly it’s not just a joke—but the best jokes never are.

John Taggart is a major American poet who, unlike a number of his contemporaries and immediate seniors, has yet to spin his wheels, who need not worry that his new work can’t compete with what he wrote when he was a young poet. There Are Birds is vibrant. It’s slim and precisely structured—precise even when whimsical. It’s a pleasure to read and to reread. To sing these songs.

____Adam Golaski is the author of Worse Than Myself. New work will appear in Torpedo, The Lifted Brow, and Little Red Leaves. He edits New Genre and for Flim Forum Press.