Big Kid

/Notorious

Directed by George Tillman Jr., 2009“Tramp” by Otis Redding and Carla Thomas sets the gold standard for bickering set to music. Over a strutting soul instrumental, Thomas hurls old-timey insults at the ever-pleading and incredulous Redding, who grows more spirited the nastier she gets.

You know what, Otis?What?You're country.That's all right.You straight from the Georgia woods.That's good!You know what? You wear overalls, and big old brogan shoes, and you need a haircut, Tramp.

Thomas’s invective is wonderful in its seemingly baseless fury, and Redding’s strangled indignation gives harried men the world over a model for dignified, if hopeless, self-defense.Thirty years later, The Notorious B.I.G. and his sometime girlfriend Lil’ Kim gave Redding and Thomas’s template a nastier spin with the track “Another” from the album Life After Death. Biggie and Kim were made of decidedly rougher stuff than their forebears—like Redding, Biggie died young, but unlike Redding, who died in a plane crash, he met his end in a mysterious hail of gunfire. Kim is an even less likely inheritor of Carla Thomas’s legacy than Biggie is of Redding’s, as she is known primarily for her exaggerated sexual persona rather than her music. Still, the pathos of their song’s scenario, coupled with Biggie’s authoritative, if characteristically misogynistic, delivery, gives it a spark that makes it worthy of comparison to the great soul duet. Unlike “Tramp,” with its attack and defense roles, both Biggie and Kim are furious in “Another,” and they aren’t shy about saying so.

You ain't shit, you fat motherfuckerYeah, whatever whateverWhatevaYou wasn't sayin that when you was suckin my dickYou wasn't sayin that when you was eatin my pussy! You a nasty motherfucker!

As the song proceeds, Biggie and Kim trade verses, accusing one another of a wide range of sexual and personal betrayals. Biggie calls her a gold digger and accuses her of sexual infidelity; Kim says she’s seen Biggie’s car outside her sister’s garage, among more explicit indiscretions. What elevates the song above simple rancor, however, is the genuine emotions that both introduce into their verses. Biggie’s part contains the lines:

Now I'm like Brandy, Sittin In My RoomPissy drunk listenin to Stylistic tunesOr the O-Jays, thinkin bout the old daysMy nigga's like, fuck that bitch, go play…

The image he presents of himself is baldly sentimental, with a self-pity that verges on the comic. The towering drug dealer, who spends most of his songs bragging about his ability to kill men and use women at will, is drinking alone and listening to old soul music.Kim’s section is even more emotional, though decidedly angrier:

…my love is concreteStashin ya heat in the passenger seatof the Nautica Jeep, we've been down for so longStill a bitch like me tryin to hold on…

Like Biggie, and most mainstream rappers of the past two decades, Kim’s lyrical persona is rooted in an indomitable pride that frequently shades into callousness. Her vulnerability here—she has been taken advantage of despite her loyalty and criminal complicity—is poignant because it is so rarely expressed. In the case of “Another,” the emotional honesty Kim conveys is probably helped by anecdotal backup. In an excellent and thorough account of the creation of the album Life After Death published in XXL magazine, she recounts that she was actually furious at him during the recording of the song. “We had a big-ass fight. I had heard about him and some girl… And I hit Biggie so hard. And he was on crutches, so I kicked his crutch on the floor!”This raw quality is one that the Notorious B.I.G. perfected in the best tracks of his short recording career, both by himself and in collaboration with others: the tough veneer melting away to reveal a surprisingly emotional, frazzled core. In fact, it is this emotional expressiveness that sets him apart from his contemporaries and future challengers to his mythic reputation. He also competes healthily in the traditional hip-hop sweepstakes nastiest sex boast, most cold-blooded crime claimed, most eloquent defense of free-market capitalism. He has many rivals in these categories, but few have approached his status as a cross- cultural hero.

| Christopher Wallace, nee The Notorious B.I.G., nee Biggie Smalls, managed to turn his obsession with sex and death into monumental pop music on the two albums completed during his lifetime. These two albums—Ready to Die and Life After Death—have very different virtues. The first is stark and efficient where the second is voluptuous and dallying. Whereas the first album thrills and shocks with its often disturbing violent vitality—“Where the cash at? Where the stash at? / Nigga, pass that before you get your grave dug / from the main thug, .357 slug”—the second is filled with more baroque imaginings of crime scenarios and sexual encounters, with guest singers, rappers, and producers contributing to make it a less personal album. For all its flaws—skits! Biggie singing!—Life After Death has the blessing of variety that Ready to Die does not. That being said, Ready is without a doubt the superior record. The relentless tales of doomed fucking and fighting are delivered with a fury and precision that is rarely matched by the generally smoother work on Life After Death. |

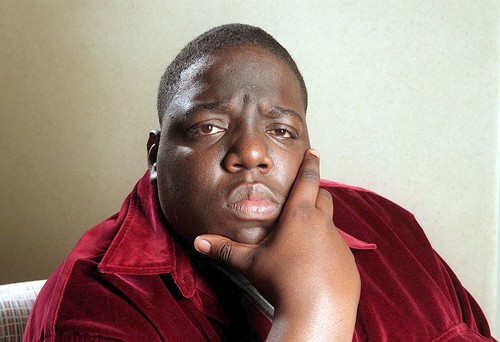

The Notorious B.I.G. on Fulton Street in Brooklyn, 1994 |

Ready to Die is a painfully personal album, seemingly designed to provoke a grim claustrophobia when listened to from beginning to end. This mood is broken for the club super-hits “Juicy” and “Big Poppa,” which were mandated by his overbearing but extraordinarily savvy producer Sean “Puffy” Combs, known most recently to the world as Diddy. It is hard to justify a great deal of what Combs did with Biggie’s legacy after his death, from using his “tribute” to Biggie “I’ll be Missing You” to send his own debut album to the top of the charts, to the travesty of the Duets album, which teamed fragments of unreleased Biggie recordings with verses from random assemblages of artists. He was unquestionably right, however, about requiring the reluctant Biggie to record the singles on Ready to Die. The unalloyed pleasures of these tracks are enduring, and they alone have guaranteed Biggie a continuing life on the radio. But they aren’t merely trifles; even the “life is good” anthem “Big Poppa” has a cloud of violence hanging over it in the repeated plea not to “shoot up the place.”The tone of the entire first album is set in the first proper song, “Things Done Changed,” which seems the most nakedly autobiographical and emotionally complex of Biggie’s entire output. The lyrics lament the rise of violence in his neighborhood and express regret for the inevitable passage of time. The opening lines of the song serve as a nostalgic preface to the largely nihilistic album to come:

Remember back in the days, when niggas had wavesGazelle shades, and corn braidsPitchin pennies, honies had the high top jelliesShootin skelly, motherfuckers was all friendly

By opening his first album with these words, Biggie displays a self-awareness of the horror of the repetitive violence that the rest of the album depicts. While Biggie can go over the top with the blood-letting (how many words really rhyme with “gat” in the end?), he doesn’t tend to revel in the scenarios the way his contemporaries in the Wu-Tang Clan do. He typically embraces the notion of crime as a necessity of ghetto life, though his social commentary doesn’t extend too far beyond the compact and memorable couplet “Either you’re slinging crack rock or you got a wicked jump shot.”“Things Done Changed” contains Biggie’s two most gut level affecting lyrics, both of which concern the relationship between parents and children. Both are delivered at a scarily intense pitch. The first—“Back in the days, our parents used to take care of us/Look at em now, they even fuckin scared of us” is merely depressing, while the second, which ends the song—“My mother’s got cancer in her breast/ Don’t ask me why I’m motherfucking stressed”—is absolutely devastating. With this line, the anger and dread that suffuses the album comes into clear focus. While there’s certainly something in the line that smacks of self-pity, the confession seems almost courageous when juxtaposed with the invulnerable shit-talking that dominates almost every one of Biggie’s songs. In this moment, before we shift into the truly sinister and ugly “Gimme the Loot, ” Biggie sounds like nothing so much as a scared kid under tremendous, intolerable pressure.

Which he was, as Notorious makes poignantly clear. While the biopic as a whole leaves a lot to be desired, one of its unambiguous virtues is that it gives one a visceral sense of how young Chris Wallace was when he became a drug dealer, a rapper, and a murder victim; he didn’t live to be 25. The early scenes of the film, featuring an ebullient man-child Biggie hiding his crack under his bed in his mother’s house and keeping his expensive sneakers and chains in a box on the roof, illustrate the allure and the difficulties of his choice to defy his mother and deal drugs instead of finishing school. Jamal Woolard imbues his Biggie with an impetuous smirk that we remember, even when it is replaced more often than not by an anxious scowl or self-important grin in the later parts of the film. In this necessarily compressed version of Wallace’s compressed life the kid in him shines through, even when he works his way up to a record deal and international fame.This big-kid quality that Woolard picks up on in his portrayal is an active part of the Notorious B.I.G. iconography, from the Afro-topped baby on the cover of Ready to Die to Spike Jonze’s brilliant posthumous video for “Sky is the Limit,” which features children dressed as Biggie, Puffy, Lil Kim and the rest lounging around a mansion and mugging for the camera. Biggie’s boast in the inimitable “Hypnotize” that “Poppa’s been smooth since days of underoos” is both hilarious and poignant, drawing out the playful element that is present even in Biggie’s often nightmarish landscapes. The fact is that despite the strikingly intimidating posture that he kept, he never fully matured lyrically. There isn’t a very strong tradition of maturity in hip-hop— its first generation of elder statesmen like Chuck D and Dr. Dre have struggled with the expectations of the genre— but even so, Biggie’s work, with its adolescent sex scenarios and garish violence, can seem particularly stunted. It takes only one listen to Illmatic by Nas, released when he was about the same age as Biggie and in the same year as Ready to Die, to understand that Biggie’s world lacks some of the shading that is possible within mainstream rap conventions. The relative narrowness of focus in Biggie’s music, however, often serves as a strength, or at least as a vehicle for an intensity and strangeness that remained nearly unrivaled until Lil Wayne emerged recently as a true contender. We listen to Biggie, and now Wayne, for the cognitive dissonance created by the combination of an out of control id with technical mastery. The pathos in Biggie’s lyrics is a young man’s pathos—the expectation of violence, the insecurity of relationships with women—and somehow his candor about these subjects set his thoughts firmly in place in a way that continues to resonate.

I know you sick of this, name brand nigga withflows girls say he's sweet like licoriceSo get with this, nigga, it's easyGirlfriend here's a pen, call me round tenCome through, have sex on rugs that's PersianCome up to your job, hit you while you working…

“Hypnotize” is explicitly about the confluence of money and sex, describing a world in which Biggie has been set free from whatever limitations he was still subject to. Biggie’s sex life—graphically recounted and imagined, and frequently involving Kim, both before and during his marriage to Faith Evans—is one of the pillars of his lyrical output, and, at least according to Notorious, one of the focal points of his biography.Over the course of his recording output, his fantasy life expands to accommodate his greater access to women and luxury items. The pre-sex crime R. Kelly collaboration “#!*@ You Tonight” continues in the exalted sex-king vein, though it lacks the virtuosic rapping of Biggie’s best tracks and suffers from the soupy R&B production that makes some of Life After Death drag. Still, one can hear the strange wheels in Biggie’s head turning in the elaborate sexual scenario he conjures, seemingly channeling Prince at his Dirty Mind finest:

Straight to yo mother's bedAt the Mariott, we be lucky if we find a spotNext to yo sister, damn I really missed theway she used to rub my back, when I hit thatWay she used to giggle when yo ass would wiggle

It’s an unusual adolescent fantasy, made palatable and funny by Biggie’s charm. You get the sense here that he is being consciously over the top even if there is still a nagging discomfort with the way he takes his sexual satisfaction for granted; the chorus after all, repeats “You must be used to me spending / all my time wining and dining / but I’m fucking you tonight.”The real questions about the line separating our enjoyment of Biggie’s ego and our disgust in it arise in tracks like “One More Chance” from Ready to Die, one of the truly nasty sex raps in a genre bulging with them. The track is a seemingly endless catalogue of sexual descriptions, promises and threats. The rhymes are insistent and tightly packed, the backing track smooth R&B with a cracking snare.

I get swift with the lyrical giftHit you with the dick, make your kidneys shiftHere we go, here we go, but I'm not DominoI got the funk flow to make your drawers drop slowSo recognize the dick size in these Karl Kani jeansI'm in thirteens, know what I mean

What do we do with this? There’s no small degree of misogyny in the proposition to “make your kidneys shift,” and the track has further come-ons that are more menacing than they are enticing. And yet a diverse swath of people has loved this music, even at its roughest. It have to do with the lack of inhibition in his words and delivery, or simply the outsize scale of all of these activities, indicating that they are intended more in jest than as threat. They are not for everyone, but for a certain temperament these puerile constructions can be wickedly funny. Biggie is eternally the fat kid in the back of the room projecting his insecurity onto the pretty girls in the front, even when he finally has the opportunity to take them out for a date . There’s a sense in “One More Chance,” and in many of Biggie’s songs, of a tension that can only be released by a thorough purging of his inner life. Sometimes he crosses the line—there’s a significant portion of his work that is best left unrepeated—but when he succeeds he convinces us of the necessity of his expression, for fear that he will otherwise be consumed by whatever's inside.And, to contrast some of his worst habits, perhaps the best piece of Biggie sex-rap ephemera is the never officially released demo he recorded of Lil Kim’s song “Queen Bitch,” presumably, as long rumored, because he ghostwrote it. There’s an undeniable thrill in hearing Biggie booming, in his inimitable baritone, “Bet I wet cha like hurricanes and typhoons / Got buffoons eatin my pussy while I watch cartoons.” There’s no sense of self-consciousness in his delivery—he fully inhabits the role. It’s a joy to imagine him in the studio, all six feet three inches and four hundred pounds, imagining himself as the 4’11'' Lil Kim getting sexually serviced. The fact that he could pull this off convincingly speaks well of his ability to transfer his appetites and attitudes into art that isn’t necessarily explicitly autobiographical.The music that the Notorious BIG recorded was often extremely violent, and some of these criminal tales—“Warning,” “Kick in the Door,” “Ready to Die,”—are among his best performances in terms of sheer verbal workmanship and delivery. But their bleakness and rage limit them to a very specific frame of mind and purpose. While even Biggie at his most romantic is fantastically coarse—his love at first sight compliment is the memorable “You look so good, I’d suck on your daddy's dick”—he captures a youthful impulsiveness and intuition that often manages to transcend the vulgarity. His legacy lies at the very delicate intersection of dark humor and plain darkness, of the weird ability to joke about sex with the heaviness of mortality constantly in mind. Even on “Suicidal Thoughts,” he finds time to slip in a farewell boast: “My baby momma kissed me but she glad I'm gone / She knew me and her sister had somethin' goin' on.” Then he kills himself.___Andrew Martin is an editorial intern at The New York Review of Books. He has worked for Publisher’s Weekly, Newsweek On Air, and Andrew Cuomo.Return to the Main Page