No Trace of Lipstick

/When is a woman writer not a “woman writer”? What does it mean to claim or resist that identity — for a woman who writes, for those who read her writing, or for those who write about her, or her writing, themselves? These vexing questions are raised repeatedly by Deirdre David’s outstanding new biography Olivia Manning: A Woman at War, not just because they are hot-button issues in current literary criticism but because Olivia Manning herself was preoccupied with them.

David’s stated goal is to prompt a reassessment of her subject, whom she considers “one of the most under-valued and under-read British women novelists of the twentieth century.” Manning certainly felt “seriously under-appreciated”: David shows her to have been constantly aggrieved that other women writers got — in her view — far more attention and praise from both the media and the public than their due (“In the early 1960s, Muriel Spark’s success became particularly irksome”; “Iris Murdoch’s amazing popular success completely mystified her”). But despite her own dissatisfaction, Manning had a long and, by most measures, successful career. “You are highly regarded,” wrote her friend Francis King to her in the late 1970s, urging her to “cease the volley of complaints”: “you have your C.B.E. [Commander of the British Empire] and you occupy a definite place of your own in the literature of our times.”

Today that “place” is due almost entirely to Manning’s two trilogies about World War II: The Balkan Trilogy — consisting of The Great Fortune (1960), The Spoilt City (1962), and Friends and Heroes (1965) — and The Levant Trilogy, comprising The Danger Tree (1977), The Battle Lost and Won (1978), and The Sum of Things (1980). Closely based on Manning’s own wartime experience in Romania, Greece, Egypt, and Palestine, the trilogies follow Harriet and Guy Pringle (easily recognizable as proxies for Manning and her gregarious husband Reggie Smith) as they are shunted about by “the fortunes of war,” the title by which the two series together were eventually known. The six novels are stories, as David says, “of dislocation and exile,” of identities as much as cities under siege, of a marriage as well as a civilization on the brink of dissolution.

If that description leads you to imagine The Fortunes of War as a sweeping melodramatic saga of romance and peril, however, you are (as I was) in for a surprise when you read these volumes: their power and, oddly, their poignancy, arise from Manning’s wry intellectual detachment rather than from suspense or pathos. Writing about The Balkan Trilogy in 1967, Anthony Burgess “identifies exactly that cold eye with which she views many of her characters — hard in her delineation of their physical awfulness and compassionate in her understanding of the wartime conditions that have brought them to that pass.” An unforgettable example of this “cold eye” in practice comes early in The Danger Tree, when a young boy is brought in from the desert after picking up a stick bomb that then explodes in his face: “One eye was missing. There was a hole in the left cheek that extended into the torn wound which had been his mouth.” Horrific as his (instantly fatal) injuries are, they do not display war’s cruelty as chillingly as his parents’ reaction, which is both wholly irrational and unbearably comprehensible:

He answered calmly enough, “My dear, of course. I expect he’s suffering from shock.”“Do you think we should rouse him? Perhaps if we gave him something to eat . . .”“Yes, a little nourishment, light and easy to swallow.” . . .One of the safragis returned, bringing a bowl of gruel and the visitors watched with awe and amazement as Sir Desmond, bending tenderly over the boy, attempted to feed him. The mouth was too clogged with congealed blood to permit entry so the father poured a spoonful of gruel into the hole in the cheek. The gruel poured out again. This happened three times before Sir Desmond gave up and, gathering the child into his arms, said, “He wants to sleep. I’ll take him to his room.”

When the visitors drive away, leaving the family to its singular tragedy, Harriet reflects on “all the other boys who were dying in the desert before they had had a chance to live. And yet, though there was so much death at hand, she felt the boy’s death was a death apart.” Details and explanations are spare and we are offered no consolation, but somehow Manning’s characteristically unflinching minimalism leaves nothing essential unsaid or unfelt.

Because of her uncomfortably clinical tone, her wartime settings, and her frequent focus on male protagonists, Manning was often credited with a “masculine” style. Elizabeth Bowen, for instance, observed that Manning’s Artist among the Missing (1949) displayed “a masculine impersonality”; the TLS reviewer of The Great Fortune “lauded her skill in not being ‘by any means a feminine novelist’” and praised especially her “objective, analytical approach.” A reviewer of A Different Face (1957) declared that “Miss Manning is one of the few women novelists who can tell a story through masculine eyes without leaving trace of lipstick on the cup.” “This is not ‘woman’s writing,’” proclaims Victoria Glendinning about The Sum of Things; Hermione Lee “declared that no other English woman novelist can write like this about war.” “Noting correctly [Manning’s] dislike of being termed a ‘woman writer,’” David tells us, Peter Ackroyd “elaborated the qualities in The Sum of Things that make her anything but that: the exploration of ‘male’ themes such as fighting and vainglory and a resolutely unsentimental prose.”

As David indicates, such assessments were music to Manning’s ears: she disdained being marginalized (as she saw it) as a woman novelist, preferring “to think of herself as a novelist who happened to be a woman.” And yet the paradox of these comments is that they too insistently return our focus to Manning’s sex: her flat affect and her ability to conjure battlefields as effectively as bedrooms are notable precisely because they are seen as defying expectations for a woman novelist. The futility of her resistance to being “pigeonholed as a woman writer” vexed Manning throughout her career.

Yet she occasionally changed her own tune when confronted, as she inevitably was, by the reality that women (whether writers or not) lived in a somewhat different world than men. The dominance of male writers in the 1950s in particular “forced Olivia to examine the often marginal position of the woman writer”: in this context, “she re-examined her long-standing reluctance to be labeled a woman writer.” She even deliberately wrote one “woman’s” novel, The Doves of Venus (1955), that David describes as her “feminist writing back to the ‘booksey boys’ at the top of the best-seller lists” — “despite a lifelong resistance to labeling novels either women’s or men’s fiction, she aimed this at her women readers.” Still, she never really reconciled her consciousness of inequalities with her distaste for any woman who “takes up a suffragette stance about her rights and abilities.” David speculates that despite Manning’s craving for acclaim, she would have sided with A. S. Byatt in rejecting the Orange Prize (now the Women’s Prize) as “sexist” if it had been established in her time.

I might speculate in turn that Manning’s combination of conspicuous personal testiness and public anti-feminism contributed to the decline in her literary fortunes after her death. She wasn’t a towering enough figure to render her cranky idiosyncrasies immaterial to her contemporaries, and unlike her genial husband, she had few (though mostly very loyal) friends — the story of her dismal and ill-attended funeral on the Isle of Wight is as rich in understated pathos as anything in The Fortunes of War. Then, she was not taken up by feminist critics keen on revising the canon — understandably, given her hostility to their efforts: “the particular voice with which the feminist writer writes of her lot is beginning to sound like a whine,” she wrote in a 1976 review of Patricia Meyer Spacks’s now-classic The Female Imagination. (Tellingly, perhaps, none of Manning’s novels were reissued as Virago Modern Classics.) She had, that is, neither popularity nor ideology on her side when she entered the lists to compete for the attention of posterity.

It probably also sped up Manning’s slide into relative obscurity (and she’s obscure enough that her name was wholly unfamiliar to two of my academic colleagues who are specialists in early 20th-century literature) that her novels are not formally innovative. Manning was a great admirer of Virginia Woolf, David tells us, but did not try “to mimic Woolf’s luminous style”: “she recognized her own talent as a writer rested less in a lyrical evocation of time passing than in the sharp delineation of a particular historical moment.” Though David may be right that Manning acted wisely based on “her unflinching assessment of her own skills as a writer,” little prestige or critical interest attached to social realism in the era of modernism — and indeed, in some circles, this prejudice against “traditionalists” (as one reviewer labelled Manning) continues to this day. That said, whether Manning’s fiction really is “traditional” should be considered an open question, given how little exegesis has been devoted to it. David’s groundbreaking work may (and, I’m persuaded, should) inspire an energetic critical re-evaluation.

Although she doesn’t say so outright, David seems also to suspect that Manning’s novels have been critically underestimated because of their proximity to memoir. This tendency is most pronounced in what she often refers to as the “transparently autobiographical” volumes of The Fortunes of War but, on David’s account, it characterized Manning’s fiction throughout her career. David is insistent that Manning’s reliance on her memory be seen not as an artistic lapse or weakness but as a strength, even an innovation — the invention of a “hybrid form”:

Olivia had carved out new territory where the literary imagination transforms recollected experience into fiction and positions it in the context of recent European history.

David concurs with a TLS review of The Balkan Trilogy that says Manning’s fiction “hardly seems like fiction,” but, again, she shapes this equivocal conclusion into evidence of Manning’s creative success:

This, of course, is really the principal point about Olivia Manning’s work. Shaping with great authority recollection of her own experience into fiction, she creates novels so much like life that they seem not to be works of fiction, which, of course, they are and are not.

But why is a defense of life shaped into fiction even necessary? Is David Copperfield considered a lesser novel because it’s known to reflect Dickens’s own biography? Do A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or The Sun Also Rises require special pleading? David does not bring up these or any other renowned examples of transmuted autobiography; presumably she considers Manning’s oeuvre different enough in either kind or degree that its specific character demands both articulation and vindication. Or perhaps this concern returns us once again to the pesky question of gender. While, historically, male experience has readily been taken as universal, women’s stories have more often been seen as singular, individual, and thus limited: David may be implicitly arguing that the autobiographical basis of Manning’s work should not be the basis for such a reductive view of its significance.

David’s story of Manning’s life is well told from start to finish, rich with contextual details and memorable incidents. “The happiest women, like the happiest nations, have no history,” says George Eliot in The Mill on the Floss: Manning’s eventful history, from her repressed provincial childhood through the turbulence of marriage and war (so closely intermingled for her) and then the difficult but creatively productive post-war decades, perfectly illustrates the converse. Much of the biography’s interest arises from Manning’s own prickly character, from what David sums up as her “caustic wit, frosty demeanor, and querulous attitude.” There’s no attempt at a soft sell here, no pretense that Manning is someone we’d all like better if we knew her better. On the contrary, though David is occasionally mildly apologetic for or protective of her subject, her biography presses home the point that intelligence and ambition can be discomfiting qualities, both for their possessors and for those around them. I actually found it refreshing to be, vicariously, in Manning’s company: I enjoyed her acerbity along with her acuity. I often imagined the presence she would have rapidly established on Twitter (which, unlike the Orange Prize, I feel sure she would have embraced). No doubt she would have had a thing or two to say about the recent attempt at Wikipedia to corral women novelists into a separate category.

But A Woman at War is a “critical biography” and so David’s pitch is ultimately not for Manning but for her work — as it should be, as it was always Manning’s writing that sustained and defined her. How successful, then, is David at sparking interest in Manning’s output, especially beyond The Fortunes of War? She wrote a lot besides, including eight other novels, two volumes of short fiction, a non-fiction book (The Remarkable Expedition, about Henry Morton Stanley’s 1886 expedition to the Sudan), and a career’s worth of essays and reviews.

David describes each of Manning’s major works in detail, and probably the most striking thing about them, collectively, is that they defy generalization. Her first novel, The Wind Changes (1937), is about the Irish “troubles”; School for Love (1951) and A Different Face (1953) are “novels of austerity, isolation, and eventual violence” of the post-war years; The Rain Forest (1974) warns Manning’s readers about “the perils of environmental neglect”; the oddest sounding one, The Play Room (1969), is a story of “sexual perversity” in which “we read of two children enticed by a male transvestite dressed like a tarted-up Queen Mary who shows them his collection of naked and anatomically correct life-size dolls posed in various sexual positions.”

Critic William Gerhardie, writing in the TLS in 1953, noted even then the discontinuity of Manning’s work, which upset “the critical narrative of artistic development treasured by academic critics” and instead encouraged readers to “jump from one pert instance to another.” Unlike, say, Angela Thirkell, whose conservative Barsetshire novels (no doubt to Manning’s annoyance) enjoyed “knockout commercial success” from the 1930s through the 1950s, Manning was neither predictable nor predictably palatable to a popular audience. In this respect, and in her “cold eye” and unapologetic intelligence, she reminds me of Hilary Mantel, whose current vogue might be a good omen for David’s wished-for Manning revival. And I’d say David has made a convincing case that such a revival would be both timely and well-deserved. Work on other neglected 20th-century writers has begun to sort out some useful analytic frameworks, but the sheer variety and manifest peculiarity of Manning’s back catalogue suggests that she will pose interpretive problems all her own.

That same range, too, while it may make her work challenging to label and market, means that there’s a novel in there for everyone. I’ve already picked up a copy of The Doves of Venus, her “woman’s novel,” but it’s actually Manning’s collected criticism that I’d like most to read, if only there were an edition of it. David quotes abundantly from the many reviews Manning wrote for the Palestine Post (an association that began during her time in Jerusalem but continued long after) as well as for the Sunday Times and the Spectator, and Manning comes across as witty, idiosyncratic, ruthless, and fearlessly her own person — that is, as just the kind of critic that’s most fun and provocative to read. “If you like this sort of thing,” she concludes of Elizabeth Smart’s By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, “Miss Smart’s prose-poem — one cannot call it a novel — will give you all you want”; Lawrence Durrell’s The Dark Labyrinth has a stale scent of the 1920s, as if someone has “spilt Willa Cather and Aldous Huxley all over it.” My favorite of her critical remarks, though, was actually made off the record: in a 1970 letter, she compares Elizabeth Bowen’s prose style to “someone eating bread and milk with their legs crossed over their heads.”

Recently an interviewer (either naïvely or with superb strategy) kicked off an internet kerfuffle by asking Claire Messud whether she’d like to be friends with the protagonist of her latest novel, The Woman Upstairs. Messud rightly scorned the question: “If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities.” But there’s plenty of evidence that women writers do feel pressure to provide likable female characters. Manning, with her preference for “alienated [male] protagonists,” might have dodged this question about her novels, but David’s biography could well provoke it. After all, one of Manning’s own closest friends nicknamed her “Olivia Moaning”: she hardly seems someone we’d want to cozy up to. The chief obligation of a writer, though, as of a character, is not that she be nice but that she be interesting, and this Manning is, in spades. “After her death,” David concludes,

Olivia’s reputation came to reside primarily in her work as a woman novelist who wrote brilliantly about men and women at war, which is fair enough given the tremendous success of the trilogies, but she also merits accolades, I would argue, for writing brilliantly about childhood, male anxiety, post-war austerity, and desecration of the environment.

“Writing brilliantly,” not being friendly, is exactly and entirely what we want from any novelist, even one who happens to be a woman.

________________

Due to her unusual name, Rohan Maitzen is often not recognized as either a “woman writer” or a woman who writes. A Senior Editor at Open Letters Monthly, she also teaches in the English Department at Dalhousie University and blogs at Novel Readings. She tries to be nice but mostly hopes that she is interesting.

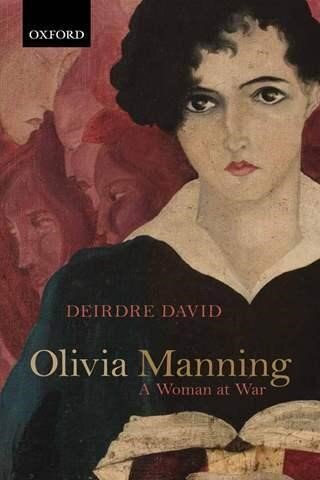

image from National Portrait Gallery, London