Shallow Sargasso Sea

/By Diana Souhami (Henry Holt, 2015)

I blame Jean Rhys.

Sure, there have been many spin-off novels besides Wide Sargasso Sea — Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs, J. M. Coetzee’s Foe, Audrey Thomas’s Tattycoram, and Geraldine Brooks’ March are only a few recent examples of this endlessly proliferating genre. But it’s Rhys’s brooding novel, which purports to tell the real story of the first Mrs. Rochester in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, that seems to have convinced many readers, writers, and critics of the logic — and, worse, the justice — of imagining such novels as corrections, even chastisements, to their originals, as if there’s a whole population of fictional characters out there who have somehow been unfairly treated by the very people who dreamed them up in the first place.

Rhys can’t actually set the record straight about Brontë’s famous “madwoman in the attic,” because the only relevant record is that provided by Brontë herself — or, rather, by Mr. Rochester, who, however morally dubious and high-handed his behavior, is not presented to us as an unreliable witness in the case of his raving, bloodthirsty lunatic of a wife. What Rhys can and does do, though, is set an alternative Bertha Mason next to Brontë’s, one that provokes us to see Brontë’s own themes and characters in sharper relief. The comparison invites us to ask questions about whose stories get told and how. It’s true, after all, that we never do get Bertha’s own perspective (which is a result of the form of Brontë’s first-person novel more than of any moral or imaginative failings on her part). So there’s plenty of room for a different story in the interstices of the original, even if there’s something vaguely illogical about the initial premise.

A similar impulse to supplement and correct motivates Diana Souhami’s newly-released Gwendolen, which retells George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda from the perspective of its other protagonist, the one not acknowledged in Eliot’s title. Daniel Deronda has long been recognized as a problematically bifurcated novel: the story of its eponymous hero’s discovery of his Jewish identity and world-historical destiny is juxtaposed uncomfortably, or so many have thought, against Gwendolen Harleth’s domestic and marital entanglements. Critic F. R. Leavis proposed fixing Eliot’s supposed mistake by “freeing by simple surgery the living part of the immense Victorian novel from the deadweight” — that is, the Jewish part. The resulting book — called, say, Gwendolen Harleth — would, he thought, be both leaner and more coherent.

Souhami’s solution is even more drastic: she doesn’t so much strip Deronda away as rewrite Eliot’s novel from the top, keeping the bare bones of Daniel’s story but sidelining it, concentrating our attention entirely on Gwendolen with the intention (eventually made explicit) of redressing the wrongs done to her by Eliot’s supposedly inaccurate and self-serving portrayal. “I was not,” asserts Souhami’s Gwendolen, “the flawed victim . . . . I am a young woman who has been unlucky and badly treated.”

Putting the pen in Gwendolen’s hand certainly yields a shorter book, but it’s not one that would give Leavis any satisfaction: in cutting away most of Daniel Deronda, Souhami sacrifices everything that’s great about Daniel Deronda. She does so, too, on the misleading pretext that Eliot’s novel fails to give us Gwendolen’s point of view, which is simply untrue. For unlike Jane Eyre, which is Jane’s story above all, seen through her eyes and told in her voice, Daniel Deronda is — like all of Eliot’s novels — related by a sage omniscient narrator who takes meticulous care to explore multiple perspectives. Reading it, we know all about Gwendolen — more and better, in fact, than she could possibly know herself. There’s no gap for Souhami’s novel to fill, in other words, and thus far from supplementing Eliot’s original it ends up being little more than a CliffsNotes précis with pretensions.

Gwendolen’s weaknesses are most evident in the first two-thirds of the novel, which repeats the entire action of Daniel Deronda, but stripped of context, elaboration, and philosophical insight. To be sure, such a reductive rendition is no better than we might expect from the self-centered and ill-educated Gwendolen we meet in Eliot’s novel, but there’s no sign that Souhami is using her first-person narration to reflect ironically on her speaker’s limitations: it’s addressed by Gwendolen to Deronda himself as an “admission of love and pain, hope and struggle,” with all the painful sincerity that implies. Souhami hews very close to the outlines of Eliot’s text: indeed, every basic element of the plot is the same, so if you didn’t actually understand what was happening in the original novel, Gwendolen would serve as a decent study aid. Souhami even lifts entire lines and sections of dialogue from Daniel Deronda, but instead of giving her novel an air of authenticity, these borrowings (which inevitably stand out from her prose for their different cadence and vocabulary) become irritants, reminders that there’s a much better version of this novel to be read. Souhami’s is Daniel Deronda “lite”: we get Daniel’s half only skimpily, through Gwendolen’s ill-informed reportage, while Gwendolen’s own half is, paradoxically, both flattened and dulled.

Here, for instance, are both novelists’ treatments of the memorable first encounter between Gwendolen and Daniel. Gwendolen — beautiful, spoiled, keen to exercise the power she doesn’t yet realize is fatally compromised by both her sex and her poverty — has run away from a pending match to the wealthy but reptilian Henleigh Mallinger Grandcourt because of discomfiting revelations about his past. She and Deronda glimpse each other across the roulette tables in the German town of Leubronn, where his intrigued observation of her as she gambles (“Was she beautiful or not beautiful?”) sets up what becomes an intricate counterpoint, in both plot and theme, between the novel’s two protagonists. His “inward debate,” Eliot tells us,

gave to his eyes a growing expression of scrutiny, tending farther and farther away from the glow of mingled undefined sensibilities forming admiration. At one moment they followed the movements of the figure, of the arms and hands, as this problematic sylph bent forward to deposit her stake with an air of firm choice; and the next they returned to the face which, at present unaffected by beholders, was directed steadily towards the game. The sylph was a winner; and as her taper fingers, delicately gloved in pale-grey, were adjusting the coins which had been pushed towards her in order to pass them back again to the winning point, she looked round her with a survey too markedly cold and neutral not to have in it a little of that nature which we call art concealing an inward exultation.But in the course of that survey her eyes met Deronda’s, and instead of averting them as she would have desired to do, she was unpleasantly conscious that they were arrested — how long? The darting sense that he was measuring her and looking down on her as an inferior, that he was of different quality from the human dross around her, that he felt himself in a region outside and above her, and was examining her as a specimen of a lower order, roused a tingling resentment which stretched the moment with conflict. It did not bring the blood to her cheeks, but sent it away from her lips. She controlled herself by the help of an inward defiance, and without other sign of emotion than this lip-paleness turned to her play. But Deronda’s gaze seemed to have acted as an evil eye. Her stake was gone.

Souhami also begins with Daniel’s inquiring eyes, but her scene is not just briefer but thinner, with none of the tactile detail or the moral complexity Eliot’s offers. “I was winning when I met your gaze,” recalls her Gwendolen; “Its persistence made me raise my head then doubt myself. It broke my luck”:

I began with pittance money, but the more I won the bolder I became. I felt destined to win a million francs before the end of play. I was blessed, the most important woman in the room. Then your gaze deflected me. Your judgmental eyes.I see that gaze now. It mixed attraction with disdain. Your eyes drew me in but implied I was doing wrong. I was beautiful but flawed you seemed to say. I felt the blood drain from my face. It was the coup de foudre (as in Bellini’s Romeo and Juliet), the start of my unequivocal love for you and your equivocal love for me.

It’s easier reading, perhaps, but far less interesting, especially because Souhami transmutes the original moment’s fraught ambivalences into the hopeless cliché of love at first sight. While in Eliot’s novel Daniel becomes — first unwittingly then unwillingly — Gwendolen’s ethical touchstone and mentor, in Gwendolen he’s primarily a romantic fantasy. “You had become so quickly my hero. My Deronda,” Gwendolen recalls; later, “I loved you from the moment I first saw you; I love you now. I would always be thrilled, shocked, and delighted to go into a room and see you there.”

A letter from her mother abruptly summons Gwendolen home from Leubronn with the news that her family’s already limited fortunes have collapsed. “The first effect of this letter,” Eliot says, “was half stupefying”:

By-and-by she threw herself in the corner of the red velvet sofa, took up the letter again and read it twice deliberately, letting it at last fall on the ground, while she rested her clasped hands on her lap and sat perfectly still, shedding no tears. Her impulse was to survey and resist the situation rather than to wail over it. There was no inward exclamation of “Poor mamma!” Her mamma had never seemed to get much enjoyment out of life, and if Gwendolen had been at this moment disposed to feel pity she would have bestowed it on herself — for was she not naturally and rightfully the chief object of her mamma’s anxiety too? But it was anger, it was resistance that possessed her; it was bitter vexation that she had lost her gains at roulette, whereas if her luck had continued through this one day she would have had a handsome sum to carry home, or she might have gone on playing and won enough to support them all.

Souhami’s rewriting, though in Gwendolen’s voice, adds nothing and loses a great deal:

I read the letter twice. I was annoyed and unconvinced by it. I was used to Mama’s laments and exaggerations and unwilling to jump to her anxious command. I had never known Mama to be happy. I feared contagion from her gloominess. My uncertain plan had been to return home at the end of September, but even before this letter I was afraid to do so. On impulse I had fled the muddle and shame that beset me there: the rich man determined to marry me, whose proposal I had almost accepted, not because I loved him or knew what love was before I met you, but to provide for Mama and be exalted in Society.

No doubt there are readers who prefer Souhami’s simpler presentation, but Gwendolen offers no revelations here that justify simply making a feebler scene out of Eliot’s original materials.

Here’s one more example to demonstrate the extent to which Gwendolen’s first-person narration — the novel’s entire raison d’être —ironically diminishes our understanding of Gwendolen herself. Driven to desperation by financial exigency and the foreclosure of every more agreeable alternative, Gwendolen marries Grandcourt after all. The marriage is miserable: coercive and humiliating. “Poor Gwendolen was conscious,” Eliot reports,

of an uneasy, transforming process: all the old nature shaken to its depths, its hopes spoiled, its pleasures perturbed, but still showing wholeness and strength in the will to reassert itself. . . . One belief which had accompanied her through her unmarried life as a self-cajoling superstition, encouraged by the subordination of every one about her — the belief in her own power of dominating — was utterly gone. Already, in seven short weeks, which seemed half her life, her husband had gained a mastery which she could no more resist than she could have resisted the benumbing effect from the touch of a torpedo. Gwendolen’s will had seemed imperious in its small girlish sway; but it was the will of a creature with a large discourse of imaginative fears: a shadow would have been enough to relax its hold. And she had found a will like that of a crab or a boa-constrictor which goes on pinching or crushing without alarm at thunder.

And from Souhami, the Reader’s Digest version, characterized by blunt brevity rather than elaboration and nuance:

I shut myself away and in despair looked at my image in the glass. In seven weeks my past life was crushed and belief in my own power gone. My will had been imperious but girlish. Grandcourt had rendered my body and spirit helpless and gained a mastery like that of a boa constrictor which goes on pinching and crushing without alarm at thunder.

So it goes for the first two sections of Souhami’s novel, like an attempt to replicate a rich symphony using only the slightest of instruments, inexpertly played.

What would make such an exercise worthwhile, intellectually or artistically? Only a strongly-felt need for an alternative to the kind of book Eliot is writing — to the whole project of Daniel Deronda itself. And two ideas do seem to motivate Souhami’s revision. The first is resistance to Eliot’s emphasis on self-suppression as the route to moral and social improvement, a motive that’s hinted at in the conversion of Daniel from confessor to love-interest. “It may be — it shall be better with me because I have known you,” says Eliot’s Gwendolen; “I said you had helped me, that my life would be better because I had known you,” reports Souhami’s, but she continues, “I could not tell you that you were my only lifeline and that I loved you.” The emphasis on her personal feelings deflects our attention from larger, more principled concerns, such as contributing to what (in the elegiac finale to Middlemarch) Eliot calls “the growing good of the world.”

Later in Gwendolen, as Souhami’s story extends beyond Eliot’s ending, Gwendolen turns her rejection of Deronda’s advice into a principle of her own:

Nor could I reach the noble self-effacing ends you advised. Each directive you gave seemed daunting, each aspiration beyond my grasp: I was not to gamble; I was to accept my suffering, nurture remorse, live to serve others. Others were no more to me than trees blowing in the wind. I chose instead to aspire to be myself, responsible for myself, to stand on my own feet.

Eliot’s doctrine of sympathy can certainly have troubling implications, and (as if in response to such criticisms) Deronda’s own role in Daniel Deronda in fact challenges her usual insistence that altruism must always guide us. But the total indifference shown by Souhami’s Gwendolen to “others” is not just a false alternative — it’s also, surely, an ethically unacceptable one. Between self-sacrificing martyrdom and ruthless individualism lies a broad middle ground defined by empathy and generosity: that’s what we all depend on and should strive for, so that “things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been.”

Why does Souhami set herself against this project? It’s a fight she appears to be having on feminist grounds, because she sees Gwendolen as “in rebellion at a woman’s lot” — Gwendolen highlights the limits Gwendolen’s sex puts on her freedom and ambitions, and Souhami’s Gwendolen herself is angrily aware that the most valuable capital she has to invest in her future is her own body:

there it was spelled out for me: marriage was the only way. My ‘natural gifts’ were the length of my legs, the curve of my breasts, the whiteness of my teeth, the wave of my hair, and the slant of my eyes.

Her worst lesson in her own actual powerlessness comes through her marriage: the wedding night is the first in a series of violent sexual assaults which she endures because she sees no recourse: “What Grandcourt had done to me, would do to me, was not illegal. I was his wife.”Here Souhami is certainly more explicit than Eliot could be (“He said it again, ‘Mrs. Grandcourt,’ then stabbed into me again and again until I bled. . . . Until he made a strange guttural sound, and I did not know if it was my blood or his seed that seeped over me”). But we don’t actually need the physical details spelled out to know what Gwendolen’s marriage means. “She had been brought to accept him in spite of everything,” we’re told in Daniel Deronda,

— brought to kneel down like a horse under training for the arena, though she might have an objection to it all the while. On the whole, Grandcourt got more pleasure out of this notion than he could have done out of winning a girl of whom he was sure that she had a strong inclination for him personally.

As for Gwendolen, she knows that “the cord which had united her with this lover and which she had hitherto held by the hand, was now being flung over her neck.” After the wedding, as she learns the limits of what she had believed to be her power over her husband,

Grandcourt had become a blank uncertainty to her in everything but this, that he would do just what he willed, and that she had neither devices at her command to determine his will, nor any rational means of escaping it.

Gwendolen doesn’t need Gwendolen, in other words, to show us that her plight is that of a woman in a world controlled by men — their laws, their power, their desires. It’s Daniel Deronda, after all, that gives us the Princess Alcharisi, who abandoned her son and her faith for a brilliant career and then declares defiantly to that son when they are reunited,

You are not a woman. You may try — but you can never imagine what it is to have a man’s force of genius in you, and yet to suffer the slavery of being a girl.

“The inmost fold of her questioning now,” thinks Eliot’s Gwendolen, faced with a similar turning point, “was whether she need take a husband at all — whether she could not achieve substantiality for herself and know gratified ambition without bondage.” The painful answer she receives is no: she lacks both sufficient talent and sufficient courage to strike out against all opposition, to create opportunity where her world forecloses it. And so, with no “possibility of winning empire” herself, as she had once dreamed of doing, she falls subject to Grandcourt’s “empire of fear.” To acknowledge the realities, and the consequences, of such social and personal limitations is not to endorse them: it’s Eliot herself who teaches us to feel, as Souhami clearly does, deeply dissatisfied at Gwendolen’s fate.

Things get more interesting in the final section of Gwendolen because, moving as it does beyond Eliot’s ending, it at least has the virtue of originality. As she comes out from Eliot’s shadow, Souhami pursues her own theme of Gwendolen’s self-actualization, focusing especially on her discomfort with her sexuality and her desire to reclaim the liberty to be herself that she lost when she became “Mrs. Grandcourt.” She takes a series of fairly random-seeming steps towards that freedom: she befriends a cross-dressing circus performer; she becomes an artist’s model, posing (a bit too pointedly) as “Marianne, goddess of Liberty”; she spends a lot of time with Deronda’s artist friend Hans Meyrick, who takes her for a ride in a hot-air balloon, from which they parachute back to the earth:

I was suspended in clear warm air above the land. Above the symmetry of roads and farms, the shadows of trees on wooded hills, I felt such freedom. I was flying high. I laughed and shouted and thought how you would deplore it, how Mama would be alarmed, how Uncle would preach a sermon, and Grandcourt not rescue me no matter if I nearly died. My heart for this eternal moment was not pressed small. My unbounded future was everywhere and everything. The fixed receipt for my happiness was not determined by a husband’s permission or Society’s approval. . . . I was in my element. . . . I was Gwendolen.

Gwendolen may be a much shorter book than Daniel Deronda, but at times like this it feels much longer. First-person narration by someone who admits she has “no particular ability or talent beyond my looks” provides a cover-story for such trite effusions, but this is clearly meant as a climactic moment, and (unlike Gwendolen herself, who fortunately drifts safely down) it falls flat as revelation or inspiration.

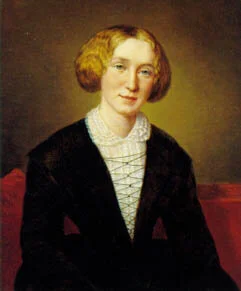

Souhami’s Gwendolen also becomes acquainted with a number of London intellectuals and writers, among them none other than George Eliot herself. They meet for the first time during the period covered by Daniel Deronda, when Gwendolen is introduced to “Mr. and Mrs. George Lewes (who were authors — both very ugly, he vivacious, she intense, her voice low, her eyes observant).” “She seemed to appraise me with disapproval,” Gwendolen thinks then, and this guarded mutual hostility continues as they meet more frequently in the final section of Gwendolen. “I was aware of Mrs. Lewes’s repeated scrutiny of me in a way I could not interpret but that seemed unfavorable,” reports Gwendolen when she and Hans join other guests visiting the Leweses at their home the Priory;

I felt weighed in the balance and found wanting. She keenly observed my appearance, though her clothes were a veritable mishmash of ill-assorted things. I thought her so plain and evidently fiercely clever that not many men would want her as their wife. It was as well Mr. Lewes was devoted. I suspect she viewed herself as ugly, which she was, hers was such a heavy face — her big nose, severe jaw, and rather tired eyes. Perhaps she had been led to believe she was ugly as often as I had been praised as beautiful.

It’s an odd metafictional gambit, bringing Eliot into this alternative universe created from the dense matter of her own novel, and one that Souhami uses as awkwardly as she does the material from Daniel Deronda. She shoe-horns in biographical summary as if anxious her readers won’t know the details — which no doubt some of them won’t, but a passage like this serves little apparent purpose in Souhami’s actual novel:

Mrs. Lewes wrote her successful novels under the name George Eliot, so I, like many of her readers, had supposed the author to be a man. George was Mr. Lewes’s Christian name, and Eliot, she said, “was a good mouth-filling easily pronounced word.” Writing earned her wealth as well as fame and financed her husband, his wife, and their offspring, whom she viewed as her stepchildren. The children called their mother ‘Mama’ and the second Mrs. Lewes ‘Mother.’

Souhami’s main interest, though, is in setting Eliot up as the antagonist against whose version of Gwendolen’s story Gwendolen itself is pitched. It becomes clear to Gwendolen that Eliot is studying her with a purpose: “I suspected she was going to write about me, which made me uneasy. I wanted to live a free, adventurous, and happy life, not become a character in a book.”If we can suspend the requisite disbelief and accept that these two women’s lives could intersect, this is a potentially interesting meeting of the minds. But rather than developing the contrast between Gwendolen’s self-interested definition of freedom and the guiding principles of Eliot’s own life and fiction (including, of course, Daniel Deronda), Souhami gratuitously belittles her predecessor, emphasizing (as too many writers apparently find irresistible) Eliot’s plain physicalappearance and reducing her motives as a novelist to pettiness and spite. “I wondered,” Gwendolen thinks,

if she dwelled on other people’s lives to deflect attention from her own, and whether she denigrated me — my beauty, youth, lack of education, talent, or sound judgment — in order to elevate herself.

Hans tries to reassure Gwendolen by suggesting that, while Mrs. Lewes “would probably write about us all . . . the hero of the story would be you, Deronda”;

You were the one she admired and lauded; she was interested in the rest of us only insofar as we impinged on you. Hans said he believed Mrs. Lewes was jealous of your interest in me because I was beautiful and she was not. She engaged with you intellectually over the history of the Jews, whereas you were physically drawn to me and desired me.

Gwendolen’s own characteristic self-absorption is (again) at best a weak cover-story for such a small-minded portrayal, not just of Eliot herself, but also, by implication, of her novel: Hans’s inaccurate comments take us back to the fundamental and inexplicable misunderstanding on which Gwendolen is based, namely that Gwendolen is unfairly represented in Daniel Deronda and thus needs a novel of her own.

Though Gwendolen continues to believe Eliot “was in awe of my appearance and suffered because such gifts eluded her, as her intellect and talent eluded me,” she does eventually conclude that Mrs. Lewes did not “dislike” her, but rather

wondered what direction there could be for me if I had no particular ability or talent beyond my looks, and no strong or determined direction like you. She understood marriage would not suit me, but did not see how, outside of marriage, I might carve my way for myself. . . . I had to brave the world with my shortcomings and still believe myself worthy of an equal place with all the rich, clever people with whom I brushed shoulders, minds, and points of view.

Presumably that is the problem Souhami thought she was solving: finding a way forward for Gwendolen that Eliot could not see, but one that also liberated Gwendolen from the moral obligation Eliot puts on all her characters. “Look on other lives besides your own,” Daniel urges Gwendolen in Daniel Deronda:

See what their troubles are, and how they are borne. Try to care about something in this vast world besides the gratification of small selfish desires. Try to care for what is best in thought and action — something that is good apart from the accidents of your own lot.

A Gwendolen who rejected this advice in Eliot’s world could never have been a heroine, but she would at least have been — like the Princess Alcharisi — a brilliant, perhaps even a tragic, symbol of defiance. Souhami gives us, instead, a haphazard Gwendolen who accomplishes nothing in particular with the liberated future her champion grants her. “So much and yet so little has happened and happens to me and within me,” she concludes;

Time leaks away, but I am not bound to the old rules, I am free, and I have my flight. I cannot be summed up or shown to have arrived.

Is this vaporous result really a better option than to be, as the original Gwendolen resolves, “one of the best of women, who make others glad that they were born”? It’s true that across her oeuvre Eliot celebrates those who live hidden lives, commonplace rather than heroic. To turn a passionate, complicated, richly-rendered character into a nonentity, however, and then sentence her to expend her energies to so little purpose besides immediate gratification, is a betrayal neither the real Gwendolen Harleth nor her author deserves. In the end Gwendolen offers no Rhys-style restitution, or even provocation; it cannot stand on its own artistic merits, either, against the rich, expansive, puzzling but profound novel on which it is parasitic.

Rohan Maitzen teaches in the English Department at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She was an editor at Open Letters Monthly and blogs at Novel Readings.