OLM Favorites: Trouble in Mind

/The underappreciated English writer J. G. Farrell was born in 1935 in Liverpool to Irish parents and died young in 1979 in mysterious, untimely, and dramatic fashion—he was swept out to sea while fishing on a rocky point near his house in rural Ireland; his body was not recovered for several weeks.

Farrell is best known for the three novels of his Empire Trilogy, Troubles (1970), The Siege of Krishnapur (1973), and The Singapore Grip (1978). Each of these works of historical fiction is set at moment of crisis for the British Empire—the first in Ireland during the Anglo-Irish War (1919-21), the second in India in the tumultuous year of 1857, and the third during the fall of British-held Singapore to the Japanese in 1942. Siege, which won the Booker prize in 1972, is the most accessible though ultimately the slightest. Grip is the most sprawling, compelling as a transition to work that never came to be and as an example of that much maligned genre, at least in Britain, the novel of ideas. But Farrell himself held the first novel in highest esteem, writing in the mid 1970s to a well-wisher: “I still feel that if anything of mine survives it will be Troubles.” I suspect he will be proven right. Troubles is a marvelous novel, funny, spry, composed of a ramshackle elegance. It’s populated by a series of vivid characters that we find moving even if not sympathetic. It deserves many more readers than it has had; it’s happy news that the New York Review of Books Classics has brought it back into print. Yet the novel is also confused and confusing, especially in its ideas about how to narrate historical events, a confusion that reflects the struggle of postwar British literature to come to terms with the inheritance of literary modernism.

At the center of Troubles—the most troubled, because least certain, character—is Major Brendan Archer. On leave in Brighton from the Western front in 1916, the Major meets and apparently becomes engaged to Angela Spencer, the eldest daughter of an Anglo-Irish family; he doesn’t remember proposing, but she signs her letters to him “Your loving fiancée.” The story of this courtship, presented offhandedly and retrospectively—such that even the Major must interpret it only through clues and traces—indicates the novel’s approach to storytelling: main events are narrated indirectly, at second hand, or obliquely, through omission. In 1919, the war over, the Major hesitantly travels to Ireland to claim his bride, who lives with her father, Edward, her brother, Ripon, and a host of aged guests, mostly women, to say nothing of the dozens of almost feral cats, at a once glorious seaside hotel called, no longer quite appropriately, the Majestic.

Angela has two younger sisters, as well, the twins Faith and Charity, who are initially away at school, but, as the political situation and the family’s finances deteriorate, who return home; their shenanigans, mostly good-natured and often lascivious, enliven the second half of the novel. The line between prank and hurt is often crossed, though, as when they plug the Major with a snowball embedded with a stone, or when they lasso a priest cycling down the drive of the house:

According to the most dramatic version … he was plucked out of the saddle and hung there swinging gently to and fro while his bicycle sailed on into some rhododendron bushes. More probably, however, the noose missed him (luckily, since it might have broken his neck) but caught on the pillion, shrunk rapidly, tightened, halted the bicycle suddenly and tipped Fr O’Meara over the handlebars. Stunned though he was by his fall he was willing to swear that as he unsteadily tried to pick himself up two smiling angelic faces were looking down on him from above. … Almost everything with those two girls… had a habit of beginning amusingly and ending painfully.

They themselves almost come to ruin, when they are nearly raped by a pair of drunken Auxiliaries. Over the course of the novel, such events escalate from scrapes and narrow escapes to full-fledged disasters. Both Edward and the Major have unrequited love affairs with Sarah Devlin, the daughter of a local banker. And the political situation in Ireland goes from bad to worse. First, a statue of Queen Victoria is defaced. Then stones are thrown, halfheartedly it seems, at Edward’s car. But eventually insurgents burn some of Edwards’ tenants’ fields, hoping that the blame will fall on Edward himself. All the while, despite the Major’s best efforts to keep the place together, the hotel slides into ruin before being finished off by the increasingly mad manservant Murphy, who sets the building ablaze. Eventually all that remains is a “great collection of wash-basins and lavatory bowls which had crashed from one burning floor to another until they reached the ground.”

Memorable as they are, it’s not so much the events that distinguish the novel as it is the characters that suffer through them. It is remarkable that someone who never married, never had children, and never lived to be old is so well able to depict people in all these stages of life. The most striking thing about these portrayals is their fundamental generosity: the characters aren’t always especially likeable, but they are treated gently, with wry humor. Edward’s mother (and thus the twins’ grandmother), Mrs. Rappaport, is a fine example. Half-blind, lost in memories of her young married life in Calcutta in the previous century—an uncanny link to Farrell’s still unimagined next novel, which would be set in nineteenth-century India—Mrs. Rappaport is a tyrant who has affection only for a particularly vicious cat. On the night of a great ball, the last in the Majestic’s long history, which Edward throws in a final effort to retain its glory, she refuses to come down without a revolver strapped to her gown. (The twins are horrified, convinced that now no one will dance with them.) The old woman conflates the present colonial rebellion with the one of her youth:

[W]hen someone had happened to mention the “troubles” to her a day or two earlier, her mind had been sent back to heaven only knew what Indian station out in the middle of nowhere with a vociferous, gesticulating, hopelessly untrustworthy rabble of natives at the gates; the women had had to be armed, taught how to use a revolver and reminded to save the last shot for themselves. Now, sixty years later, on the one night in years that it mattered, the old lady had remembered her elementary weapon training, found her departed husband’s revolver and, thin lips quivering, buckled it on.

The old woman is deranged—but, perhaps, not quite. Events will soon prove her caution more well-founded than deluded.

Our awkward relationship with Mrs. Rappaport is typical: we don’t fully identify with any of the novel’s characters, and yet to some degree we identify with them all. That’s true even of the Major. As he’s the protagonist, we might expect him to command our full sympathy, especially since he’s so decent. Yet the Major is also standoffish, even priggish. Ultimately, Farrell’s characterization mimics the Major’s peculiar nature: at once drawn to others but also repelled by them, at once desperate to make attachments and always interested in others but also unable or unwilling to consummate that desire.

Because the novel follows the Major most closely, we can at least try to understand his reserve. It might be a function, for example, of his traumatic wartime experiences. Less explicable, however, are the other inhabitants of the Majestic. They are evasive and irresolute; the only thing certain about them is that, like the hotel itself, they have all seen better days. This is especially true of Angela, who at tea on the day of his arrival regales the Major with her past romantic exploits before promptly taking to her sickbed, from which she never reappears.

This odd development culminates in the first surprise of the novel, one that, retrospectively, given the ruin that is to follow, isn’t surprising at all: Angela dies. She thereby thwarts the Major, who had been planning ways to break off the engagement and leave Ireland but who had been unable to put those plans into actions because of her unavailability. He is left with only his embarrassed dissatisfaction and a final letter from Angela, which itself gets left behind, tantalizingly unopened, when the Major is forced to return to England to attend at the deathbed of his only surviving relative. The Major later finds the letter right where he left it, on the mantelpiece in the disused bar, when he returns to the Majestic more than a year later. Farrell characteristically prolongs the suspense almost excessively—before deflating it when the letter offers no revelations.

Further bathos arises on the Major’s arrival in London, where his elderly aunt proves not as sick as her doctor had made her out to be. But even this reversal isn’t definitive; several months later she takes a turn for the worse before finally succumbing (or, as the novel puts it, “vindicat[ing] herself by dying”). These sorts of attenuations and frustrations—a mixture, for the Major, of guilt and vexation and repressed emotion, and, for the reader, of black humor—are typical of Troubles, in which many significant events happen offstage. Further examples include Ripon’s scandalous marriage to a parvenu Catholic girl, the manservant Murphy’s descent into madness, and Edward and Sarah’s unhappy love affair, to say nothing of the increasingly incendiary outbreaks of violence in Ireland as a whole and the countryside around the Majestic in particular.

The effect of these obliquely rendered events is paradoxically heightened by the inability of anyone or anything in the novel to be clear and direct—including its title. “The Troubles” is a common term for the conflict between Protestant unionists and Catholic nationalists in Northern Ireland. But it is unsettlingly euphemistic: how can these violent historical events be no more than troubling? Of course, in the sense of muddying, confusing or making turbid, trouble is indeed what we experience in the novel. And Farrell has played with the expression, generalizing from “the troubles” to “troubles”; his novel, he hints, won’t just be about politics, it will be about other sorts of worries too, but politics will always shade those worries.

Moreover, as the very idea of euphemism suggests, both political and personal troubles will be indirect, hesitant, even confused. And that’s just what we find in Troubles. For example, on the afternoon of the Major’s arrival, Edward leads the Major and other male guests, whom he has armed with a haphazard assortment of weapons, including a javelin, a pair of rapiers, and an old service revolver, on a chase through the grounds of the estate, convinced that he has seen a “Shinner” (that is, a member of the Sinn Fein). The hunt comes to nothing, but along the way Angela’s brother, Ripon, tells the Major about a shocking incident at a tennis party at a nearby country house that points to the confusion of the period.

A bicycle patrol of the Royal Irish Constabulary had found two individuals “tampering” with a canal bridge and set off after them. One of the men jumped on his own bicycle and tried to out-pedal the police. His plan goes well at first: the police collide with each other while attempting to ride without using their hands (the better to shoot with). But then the chain comes off the Sinn Feiner’s bicycle, and he flees into the estate where the tennis party is underway:

What a shock the tennis players and spectators had got when all of a sudden a shabbily dressed young man had sped out of the shrubbery and across the court to gallop full tilt into the wire netting (which he evidently hadn’t seen)! Under the impact he had crumpled to his knees. But though he seemed stunned, almost immediately he began to pull himself up by gripping the wire links with his fingers. Then someone had hurled a tennis ball at him. He had turned round as if surprised to see so many faces watching him. Then another tennis ball had been thrown, and another. At this the man had come to his senses and veered along the netting in search of an opening. Not finding one he had leaped up and clung to the netting to drag himself upwards. But by now everyone was on their feet hurling tennis balls. Then one of the women had joined in, throwing an empty glass but he still managed to pull himself up. Someone… had shouted for them to stop. But no one paid any attention. A tennis racket went revolving through the air and only missed by inches. Someone tore off his tennis shoes and threw them, one of them hitting the fugitive in the small of the back. He had paused now to gather strength. Then he was climbing again. A beer bottle shattered against one of the steel supports beside his head and a heavy walking-shoe struck him on the arm. Then, at last, a racket press had gone spinning through the air to hit him on the back of the head. He had dropped like a sack of potatoes and lay there unconscious. But when the breathless, red-faced peelers had finally arrived panting to arrest their suspect it was to find the tennis players and their wives still hurling whatever they could find at the prone and motionless Sinn Feiner…

The scene is horribly vivid, despite its indirection—it is told by someone who heard it second hand and even that re-telling is re-told indirectly, by the omniscient narrator rather than by the original speaker. In fact, much of its force comes from the anonymity of the actors, which is emphasized by the passive constructions (a tennis racket “went revolving through the air”; a racket press “had gone spinning through the air”); the actions seem that much more forceful, vengeful, and horrible for our inability to assign them to individuals.

This strange detachment is central to the passage’s tone, which, like much of the book, is funny about things that aren’t that funny. Sometimes Farrell’s humor is more straightforward, as when the old women who inhabit the Majestic, faced with another coming winter, are said to be “funneled towards the dreadful gauntlet of December, January and February which most of them had already run over seventy times before, reluctantly forced through it like sheep through a sheep dip.” Or when the twins, who have come across a sex manual, offer their father tips from the back seat of the car where they have been forced to accompany Edward on lengthy drives through the hostile countryside in his attempts to woo a wealthy young widow (“’Oh for heaven’s sake grab her, Daddy’”). Or when Edward, incensed that one of his dogs has killed yet another chicken, thinks to teach the dog a lesson by tying the dead animal to the dog’s neck, the main result of which is that he has to lift the dog over stone fences when they are out hunting. (Much later, the same dog dies and Edward is so insistent about burying the dog under a particular tree, despite its roots, that he buries the dog standing up.) Farrell, in other words, can make you laugh out loud.

But most of the time, as at the tennis party, that laughter is shadowed by menace. Late in the novel, for example, the stone “M” in the hotel’s marquee crashes down from the building’s façade and demolishes the tea-table that one of the hotel’s denizens, a deaf old lady, is sitting at. Her indignant complaint to Edward—“She had maybe closed her eyes for a moment or two. When she had turned back to her tea, it had gone! Smashed to pieces by this strange, seagull-shaped piece of cast iron (she luckily had not recognized it or divined where it had come from)”—is not about her near-death, about which she, like many of the characters, is ignorant even in the face of pressing evidence to the contrary, but about her ruined tea. Neither this scene nor the tennis attack would be out of place in a Keaton or Chaplin film. But the slapstick shades into something darker, and our response becomes uncertain, our laughter stops short. There’s a difference between the man’s running full tilt into the unseen net and his increasing fear and desperation, his vulnerability emphasized by the description of the place of his wounds: the small of the back, the back of the head. By contrast, the vehemence of his attackers is emphasized by the image of a man tearing off his own shoes and turning them into weapons, and the repetition of the word “hurled.”

Our interpretation of Ripon’s story changes yet again when he concludes: “’The thing is, it turned out later that this fellow wasn’t a Shinner at all. He was just repairing the bridge with another workman.” The Major has already protested, incredulous at the story: “’Frankly, I find it a bit hard to believe that people would throw things at an unconscious man’.” His disbelief shows us his values: the thorough-going decency that always verges on naivety, even quiescence (though the Major is a veteran of the Western Front and images of what he experienced there return to him unbidden throughout the book). He is beholden to standards of comportment that his own experiences no longer let him fully believe in.

The two stories of chasing false Shinners highlight Farrell’s theme of misunderstanding and deceptive appearances, but also, more literally, point to the violence that will become much more implacable as the book continues. In an inversion of Marx’s formulation, what begins as farce takes on an increasingly tragic aspect, as even the isolated countryside around the hotel becomes lawless and dangerous. We hear of attacks by resistance fighters not just against the British army and their representatives but also against civilians, and then reprisals by those forces, these too often levied at innocent bystanders. As time passes, though, it becomes less and less clear who is innocent and who is not.

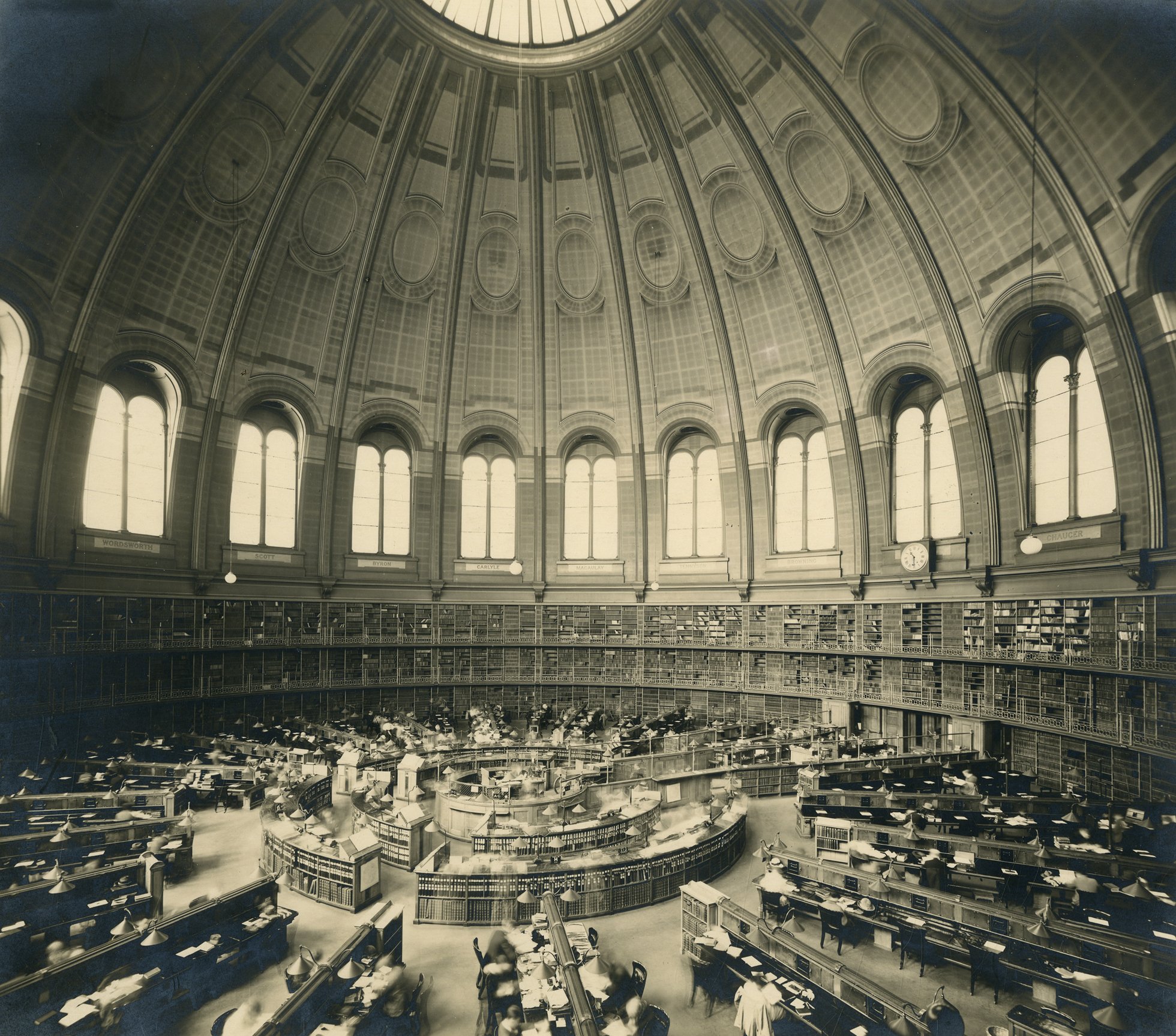

We learn of these events through excerpts from contemporary newspaper accounts, product of the weeks Farrell spent in the British Library researching the novel’s background. They are evidence of a particular idea of time and history, one organized around discrete but ramifying and increasingly consequential socio-political events. As such, they offset the different notion of time evident in the novel’s immediate focus on the Majestic and its environs. The Majestic sometimes seems timeless or outside of time, with its long-term denizens and guests who return each year even though the place is barely habitable. But time is present in the inexorable creep of decay and ruin. In this way, the Majestic allows Farrell to rethink history and its relation to narration. What would it mean if the kind of narration required by history were a joke, especially a shaggy dog story, like the buildup to a nonexistent revelation in the story of how Angela feels about the Major, rather than a list of one damn thing after another?

This question perplexed Farrell during the composition of Troubles. He resisted what he thought of as the tyranny of plot but he felt drawn to it as well, both as a practical necessity (publishers and readers seemed to want it) and as an aesthetic imperative (novels needed to be propelled by something; they needed to be organized—otherwise what made them novels and not just a set of disassociated impressions?). For Farrell, the turn to plot went hand in hand with a turn to history. In this he was representative of a larger literary trend. Beginning after the war, many British novelists turned to historical subject matter. These included writers of Farrell’s generation, including Paul Scott and Penelope Fitzgerald. But many writers of an earlier generation—such as Rebecca West, L. P. Hartley, Olivia Manning, and Richard Hughes (with whom Farrell struck up a close friendship in the early 1970s)—made a similar shift.

Of these writers, the most influential is Jean Rhys. Like the others, Rhys makes the turn to history as a way to react against the literary modernism of the interwar years. What makes Rhys such an interesting case study is that most of her output—four indelible novels and a collection of short stories—is today considered a canonical example of modernism. Rhys vanished from the public eye throughout the 1940s and 50s, and her career was resurrected in the 1960s only when the BBC went looking for her heirs (they assumed she was dead) in order to broadcast a dramatization of one of her novels. Heartened by this interest, Rhys wrote and published the work for which she is best known today, the novel Wide Saragasso Sea (1966), a retelling of Jane Eyre.

Farrell met Rhys in the years following her reappearance. He once had lunch with her and their mutual friend Sonia Orwell, and he marveled at the aged Rhys, already more than half-lost to alcoholism: “she is incredibly old and frail and her voice is rather weak: but I liked her very much.” It was not simply the 81-year-old woman he appreciated, but also the writer with direct ties to modernist literature, the one who spoke casually of Djuna Barnes and James Joyce as acquaintances. “She was like a fly in amber,” he concluded in a letter to his friend and former lover Carol Drisko. Little did he know that the ties that would bind him to Rhys would have as much to do with time and mortality as with literary history. Rhys died three days after Farrell in August 1979; their obituaries appeared on the same page of the newspaper.

They make a compelling pair, the woman who came back from the dead and the man who died too young, for their encounter sheds light on the structure of Troubles and the way its historical perspective is haunted by the specter of literary modernism. Modernist writers turned against history in their fiction. For them, historical fiction was an outdated form based on dubious, untenable principles: an epic depiction of the sweeping forces of historical change aimed at affirming human progress. Modernism, by contrast, valued the idea of the present moment. Its aesthetic innovations are quixotic attempts to represent and thus grasp this shifting, elusive entity. For this reason, there is no modernist historical fiction. Modernist novels that do reference history—Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928), for example—do so only to ironize the idea that the past has explanatory or ordering powers. History, in the first forty years of the century, is replaced by the past, and the most characteristic relation to the past, as experienced in the trenches of Flanders, is traumatic. To modernist writers, then, the linear progression of classical narration is impossible.

After WWII, the tenets of modernism themselves come to seem suspect, a burden that writers feel they must escape. Farrell was like Rhys in wanting to shift from modernist absorption in the present moment to postwar fascination with the power of history. Farrell’s rather lengthy literary apprenticeship—three novels that received tepid reviews, the gist of which was that Farrell had not fully digested the influence of Nabokov, Beckett, and Sartre—led him to a personal crisis. What kind of a writer did he want to be? In the end, Farrell reacted against his modernist predecessors, finding something wanting in their attempts to eliminate or at least contest narrative conventions, in their suspicion of history. The Major speaks for Farrell when he muses on the way an individual event (he is thinking of an attack on an Englishman he witnessed in Dublin) can lose its shock value and become just one of the “random events of the year 1919, inevitable, without malice, part of history.” He goes on to distinguish history from mere quotidian living:

A raid on a barracks, the murder of a policeman on a lonely country road, an airship crossing the Atlantic, a speech by a man on a platform, or any of the other random acts, mostly violent, that one reads about ever day: this was the history of the time. The rest was merely the ‘being alive’ that every age has to do.

The Major’s comment seems directed at Woolf’s idea that the most significant parts of life were what she called “moments of being,” opposing it by valuing a more traditional sense of what constitutes history (not the daily business of being, but the public events of politics).

Yet Farrell was unable to return to the certainties of earlier models of historical fiction. These acts are, after all, “random,” not fitting easily in any meaningful order or pattern. Hence Farrell’s irony, his hesitancy, his unwillingness to judge historical events clearly. After all, the traditional historical novel and its belief in progress failed to tell the story of all those who were on the wrong side of history. Thus Rhys’s revisionism, imagining the back-story of Bertha Mason and her Caribbean background and putting it at the center of the novel rather than at the periphery, as it is in Bronte’s novel. Farrell’s Empire Trilogy was motivated by similar concerns. Significantly, however, neither Troubles nor its successors are actually told from the perspective of those contesting British rule. Farrell’s preferred rhetorical mode is irony: the books examine dissolution from within. The risk he takes is that the presentation will be too subtle. This is presumably what Farrell meant when he worried to a friend, as he awaited the verdict of his editor on the fate of the book, that he had misrepresented the novel: the editor “feels apparently that not enough really happens in the book. I suppose I must have led him to expect that the British Empire would collapse on stage, rather than in the wings.”

Farrell’s theory of history—that events matter but they are best represented obliquely or ironically—is part and parcel of his theory of the novel. Reflecting on his previous work and anticipating the book that would become Troubles, Farrell wrote in his diary in February 1967 about the need “to think more deeply about plots, about events, about binding books together with some sort of homogeneity” and, a few weeks later, about the need for a form, so that “things can begin to fall into place, having a place to fall into.” It wasn’t until he took a trip to Block Island and came across the burned ruins of the Ocean View Hotel that Farrell realized the “place” he needed to structure his book around could be literal. Farrell finally had a way to solve the problem that had bedeviled him—the need for something at the center of a novel that “must be substantial like the stone in a peach and … must exist before one can ever begin to start thinking constructively.”

Characteristically, Farrell resolved his struggle with form ironically—his structure would be the unraveling or undoing of structure, both politically, with the end of the British Empire, and formally, in a way of life centered in a representative location. What better place to think about the transience of a particular class or group of people than a hotel? Even the novel’s narration gives a sense of unraveling. It begins, like DuMaurier’s Rebecca, by invoking destruction:

In those days the Majestic was still standing in Kilnalough at the very end of a slim peninsula covered with dead pines leaning here or there at odd angles. At that time there were probably yachts there too during the summer since the hotel held a regatta every July. These yachts would have been beached on one or other of the sandy crescents that curved out towards the hotel on each side of the peninsula. But now both pines and yachts have floated away and one day the high tide may very well meet over the narrowest part of the peninsula, made narrower by erosion. As for the regatta, for some reason it was discontinued years ago, before the Spencers took over the management of the place. And a few years later still the Majestic itself followed the pines into oblivion by burning to the ground—but by that time, of course, the place was in such a state of disrepair that it hardly mattered.

Here again we see Farrell’s simultaneously longwinded and elegant style. Paragraphs, if not always sentences, run long in this book; there’s a hypnotic flow. The pages turn rapidly even though not much happens, except when these longeurs are punctuated by intimations and eventually bursts of violence. The most striking thing here is the panoply of various narrative times. There’s the unspecified past (”in those days,” “at that time”) that at first seems to be the time of the Major’s arrival in 1919 but in fact can’t be, since we learn that the regatta had been discontinued “years before.” There’s the time after that past, when the Spencers took over the hotel, and then there’s the past of its destruction, and, most curiously, a present “now” that is nowhere else featured in the book.

We might expect that present moment to be the privileged vantage point from which all the vagaries and depredations of the past make sense. But that’s not the case, since Farrell’s historical novel is one in which things fall apart. By structuring the book around the ruin, at first gradual and later hasty, of the Majestic, a stand in for the Anglo-Irish ascendant class, Farrell paradoxically gave his writing new momentum. Farrell had always struggled with plots, and even here the “plot” of destruction—of the hotel, and of the class of people who inhabited it—is hesitant, relying as it does on heaps of generalized, retrospective narration. For example, in his perambulations through the vast expanse of the hotel, the Major is forever coming across instances of damage and decay, none of which he actually sees happen, until the hotel’s spectacular and dramatic end. Some sample sentences: “All this time the hotel building continued its imperceptible slide towards ruin”; “[The Major] worried about everything, about the cats proliferating in the upper storeys, about the lamentable state of the roof (on rainy days the carpets of the top floor squelched underfoot), about the state of the foundations, about the septic tank, about the ivy advancing like a green epidemic over the outside walls (someone told him that far from holding the place together, as he had hoped, it would pull it to pieces with all the more speed.” This is great stuff, but it shows by summarizing rather than by direct presentation.

Farrell is struggling here with the problem of how to narrate something that it is intrinsically undramatic because uncapturable: the passing of time understood as depredation. A film could use time-lapse cinematography to make this transformation dramatic. The novel has its dramatic moments—during a storm, the roof of an entire wing comes off, “the slates blowing away into the swirling rain… the black hole grew steadily larger like a woolen sleeve unraveling”—but mostly it relies on a model of incipient anxiety: things keep getting worse, bit by bit, but the change itself can’t be seen.

This difficulty is political as well as aesthetic: one might equally ask how best to capture the gradual decline of an Empire. What constitutes an event here? To what extent is decline (as opposed to catastrophe) narratable? One solution is sheer length—as if the time of the reading were to mimic the time of the story. There are plenty of twentieth-century novels that aren’t plot driven. Of those, Farrell particularly valued The Magic Mountain (1924), Thomas Mann’s novel about the practical but impressionable Hans Castorp, who goes to a sanatorium in Davos on a three-week vacation and ends up staying for seven years. Like Castorp, the Major ends up staying in an enclosed, isolated space for much longer than he initially plans. Indeed, he only leaves once the place burns down around him and he has narrowly avoided death at the hands of Irish nationalists, who leave him for dead buried in the “sandy crescents” referred to in the novel’s opening paragraph. The Major escapes, thanks to the help of the old ladies he has both battled and protected in his time at the hotel and the ministrations of the old and only apparently doddering Dr. Ryan of Kilnalough.

Ryan, who shouts at the others to stop their attack on the innocent man at the tennis party, is forever dilating on the flimsiness of people (and, we might add, the buildings they live in, especially when they live in them as temporarily as they live in a hotel). Late in the novel—he is suturing the Major’s wounds, but forgets what he is doing and has a little nap between finding the needle and stitching him up—he muses:

…people are insubstantial. They never last. All this fuss, it’s all fuss about nothing. We’re here for a while and then we’re gone. People are insubstantial. They never last at all.

This could be sententious, a dubious, Olympian view of time in which the human doesn’t matter at all. But that disdain is qualified both by the doctor’s frailty and the novel’s clear interest in and even tenderness for people. At least that’s one way to make sense of a puzzling moment three-quarters of the way through the book, a parenthetical exclamation that isn’t attached to any character in particular: “One day we shall vanish. But for the moment how lovely we are!” We could then read the exclamation mark as serious, not ironic.

Yet of these two sentences it is actually the first that is the most confusing. “One day we shall vanish”: here as elsewhere the novel seems to believe in the inevitability of ruin. But what does this belief imply? What Troubles lacks, and what makes me think that Farrell, even in this marvelous, enjoyable novel, is a writer who will always be second-tier, who will always suffer the dubious fate of being newly rediscovered, is a clear idea of the meaning of destruction. The novel takes, in the end, too little distance from the Major, seeming to share rather than critique his confusion about events in Ireland. It seems to be the book as a whole, rather than just the Major who thinks:

Meanwhile in Ireland, the troubles ebbed and flowed, now better, now worse. He could make no sense of it. It was like putting out to sea in a small boat: with the running of the waves it is impossible to tell how far one has moved over the water; all one can do is to look back to see how far one has moved from land.

The narration is weird here. “He could make no sense of it” aligns us with the Major, suggests that what follows will be his thought. But the use of “one” rather than “he,” which would be implied by free indirect discourse, takes us out of his mind and makes the thought seem to come from the narrator. The failed search for landmarks, for a firm place from which to make judgment is, at its best, a version of tout comprendre, c’est tout pardoner. But at its worst it’s a helpless shrugging of the shoulders, even an expression of ignorance that could turn a blind eye to oppression.

In that regard, it is significant that the novel never offers the perspective of those for whom destruction of an old, oppressive order might be in some ways generative, even if the violence of that destruction is hard to sanction. We are always watching that falsely accused Shinner from the outside. The horror of that attack—expressed directly by Dr. Ryan and experienced indirectly by readers as we laugh nervously—isn’t accompanied by any consideration of the uses and abuses of violence. We are here both literally and figuratively in the country of Yeats’s “terrible beauty.” His great poem “Easter 1916” is ultimately more compellingly ambivalent about the connection between destruction and generation than Troubles.

Indeed, Farrell’s novel has next to nothing to say about generation. Significantly, eros ultimately plays no real role in the novel, despite the initial donnée of the befuddled engagement and the lengthily developed story of the Major’s infatuation with Sarah Devlin. I haven’t spoken of her here, even though the novel does at length, because the novel throws her over, even more fully than she does the Major, when it concludes that, after many weeks of thinking of her painfully, of having his love for her perch in him “like a sick bird”, “one day, without warning the bird left its perch inside him and flew away into the outer darkness and he was at peace.” Despite the final word of that sentence, the novel abandons eros; it is more interested in thanatos. As such, it leaves the reader unsure where to stake his claim, where to identify.

This imbalance is all the more curious given the book’s general tone of care and affection. Like the Major, then, still trying to believe in standards that he himself helped to destroy in the war, the novel upholds something it doesn’t seem to value. This isn’t cynical, but it is confusing. So too is the novel’s attitude to history, especially in the wake of the challenges posed by modernism. If we take modernism to be like the war that was so central to its artistic creators, then we might find Farrell unrecovered from its trauma—unwilling to accept its disjunction and fragmentation but unable to attain the certainties and beliefs of the period before it, a period that he at once longs for and rejects, like the “those days” of its opening phrase. Troubles, indeed.

Dorian Stuber is an Assistant Professor in the English Department at Hendrix College, where he teaches British Modernism and Holocaust Literature.